Edvardas ŠUMILA | New York Scenes and Echoes from Lithuania: Jonas Mekas’ Musical Milieu

As I was flying to New York for the first time last year, on August 17, if I recall correctly, I took one book for my trip which I wanted to read, Here Is New York by E. B. White – many friends had recommended it to me. It is a classic, perhaps one of the most famous texts on the city, written seventy years ago in 1948, one year before Jonas Mekas came to Brooklyn at the end of 1949.

The essay described life in post-war New York. I was carried away by the New York of the late 1940s, and, truly, the city has changed tremendously. However, I was also astonished by my later findings as to how many things have actually remained unchanged, especially in terms of the feeling, despite the transformations in city development, demographics, policies, movements, and other things.

I immediately knew that I wanted at least to get to see Jonas Mekas – a filmmaker and a poet. For me he was one of the symbols of New York, he had been there for the whole second half of the 20th century and was still active in shaping the cultural atmosphere and life of the city until the very last.

I wondered what could have been happening in the young mind of Jonas Mekas at the time when he came to New York. As I was guessing, too, whether his picture of it could have been similar to E. B. White's. “You have to see New York at night,” wrote Jonas in his diary at the time, “from the Hudson, like this, to see its incredible beauty. And when I turned to the Palisades – I saw the Ferris wheel all ablaze, and the powerful searchlights were throwing beams into the clouds.”[1] I was surprised to learn later from his son Sebastian that E. B. White’s book was actually the one which Jonas Mekas would buy numerous copies of and give to people as an introduction to New York.Apart from all the prolific work and the legacy Jonas Mekas has left us, what was barely talked about but is nevertheless fascinating was his musical milieu, springing both from his environment, friends and influences, as well as his own musicality, which I began to be aware of not so long ago.

Jonas Mekas was extremely musical in everything he did. It was, of course, in his poetic nature, in his identity as a poet – we know that poetry is morphologically and historically close to music. Yet it is also true that everything he did had not only a certain rhythm, sometimes a swing, and sometimes something more lyrical, it also had a melody. So much in his life seems to have been sung and strongly perceived.

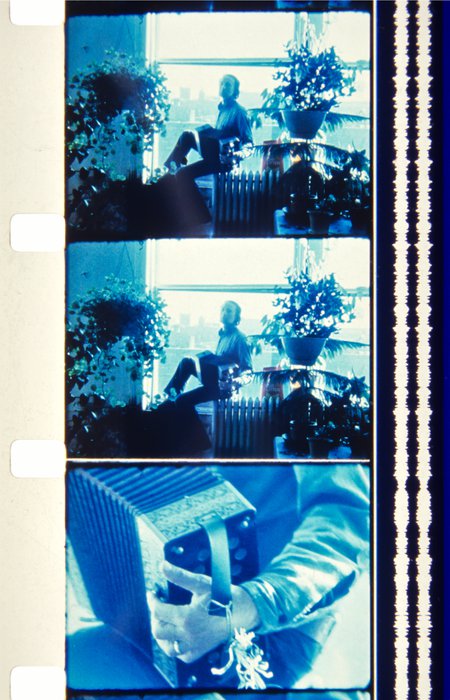

In one of the parts of his first major diary film Walden, we can hear Jonas’ words “I make movies, therefore I live,” which couldn’t be truer in his case, nevertheless, he said it by accompanying himself on a bayan, an instrument which apparently never left his every-day life. So where should we look? Where should we search for the roots to this life imbued with music all along the way?

Well, one of the stories laid down in his diaries, published as I Had Nowhere to Go, where he recalls his passion to learn to play music – already adept in playing mandolin when he was twelve, he took up the violin, learning to play it all by himself. “I played two winters that way. I learned to read the scores, and I played Mendelssohn and Paganini.”[2] The story ended with young Jonas having to give it up – his neighbours ‘baptised’ him Paganini, and he didn’t like this kind of name-calling. Nevertheless, music never left him.

I met with Sebastian Mekas to talk about his late father before I left New York for the summer. In my view, Sebastian himself is proficient in music and is very much into ethnomusicology, as well as linguistics. It is his very individual musical sensitivity that helped me to map Jonas’ musical world as well.

We met at Mekelburg’s – a grocery store, which turns into a bar later in the evening. This was right next to the former sugar factory in Williamsburg, the one in which Jonas Mekas briefly worked when he had just come to New York, and where many Lithuanian immigrants also worked in the late 1940s. Williamsburg, the place where I am staying right now, was actually very much Lithuanian fifty years ago, with the only Lithuanian catholic church from those days also being located there. Another branch of Mekelburg’s was on Grand Avenue, in Clinton Hill, Brooklyn, approximately halfway between where I stayed for my first seven months in New York City and where Jonas and Sebastian’s home was.

I never actually got to meet Jonas Mekas properly, I only had a chance for a brief conversation with him during the launch of the latest Film Culture issue. I knew that he was just a few blocks away, but the time wasn’t right. Jonas Mekas continued to work until the very end, saving his energy for what were the most important things and people. I was happy to visit their loft a couple of months after he passed away and see so much of his work in progress, his books, the cat whose name is Pie-pie, and I even had the chance to blow a daudytė, a type of Lithuanian folk wooden trumpet, perhaps five feet (1.5 meters) long, characteristic of the region he was from, which he owned and played occasionally.

Sebastian told me that pretty much everybody played an instrument in young Jonas’ family, so even if none of them was trained professionally, the environment was absolutely imbued with music. He used to play a bayan and owned a bandoneon – an Argentinian-style accordion – later in his life. The living conditions in Semeniškiai were pretty much like one would imagine them to have been in the 19th century. And since Jonas and his brother Adolfas had fled Lithuania, their family felt the consequences for quite a long time too. It was kind of punishment that their mother was not provided with electricity even into the late 70s, and many members of their family couldn’t travel very much; neither to the countries of the Eastern bloc nor those of the Soviet Union.The music springing from the Lithuanian countryside remained with him all of his life, and we can see it very well in his Reminiscences of a Journey to Lithuania, a documentary about the first visit back to his birthplace in the 70s. Jonas Mekas longed for the authenticity which the folk songs had when he was growing up in Semeniškiai. He would often state that many of the songs he heard after the restoration of independence in 1990 sung by young people who learned them during Soviet times were corrupted in some way, a number of the stanzas forgotten, the melodies and harmonies made to conform to the ‘norms.’ He, on the other hand, remembered them as they were, as they were sung in Semeniškiai and the neighbouring villages.

Displaced Persons’ camps where Jonas has spent the years between 1945 and 1949 surely didn’t offer a lot of choices in cultural life, especially as compared to New York. Yet, looking at his writings of the later years, you can see how he judges all the performances of modern music of the time, comparing ones heard in Europe and New York. On December 18, 1954 he wrote: “We went, with Elizabeth, to Kaufman Auditorium for an evening of modern dance and music. L’Histoire du Soldat [by Igor Stravinsky]. Despite the fact that I like this work very much, this tasteless, mediocre production made me almost hate it. I still remember Karl Heinz Stroux’s beautiful production in Kassel, six years ago.”[3] He enjoyed the Lyric Suite by Alban Berg very much though at the same event.

When Jonas came to New York, he was like a dry sponge, as he would have put it – a garbage can, who could absorb anything that was thrown at him. So they would go to Carnegie Hall with his brother, or to the old, now demolished opera house and wait for the intermission, so they could sneak in without a fee – and that was quite an interesting way to get oneself introduced to a variety of music: skipping the first act of an opera, or a part of the concert, but trying to soak in as much as New York could throw at them. It’s worthwhile noting that Jonas Mekas came to New York at an exciting time, which connected much of the older culture from the first half of the century with the emerging new – avant-garde one, in which Jonas took an active role. He saw the old generation of jazz celebrities from the bebop era, replaced by cool jazz later on. The ballet world still had George Balanchine and Igor Stravinsky, and Bruno Walter was leading the New York Philharmonic.

The decision of Jonas and Adolfas to eventually distance themselves from the Lithuanian community in Williamsburg and start life in Manhattan was a pivotal one. In April of 1953, they settled at 95 Orchard street and, according to Jonas, that’s where another stage of his life immediately began. That’s when he has organised the very first avant-garde film screening at Gallery East that has just opened on Avenue A and 1st Street. From that point, their future plans were decided, and the Film Culture magazine was published soon afterwards.

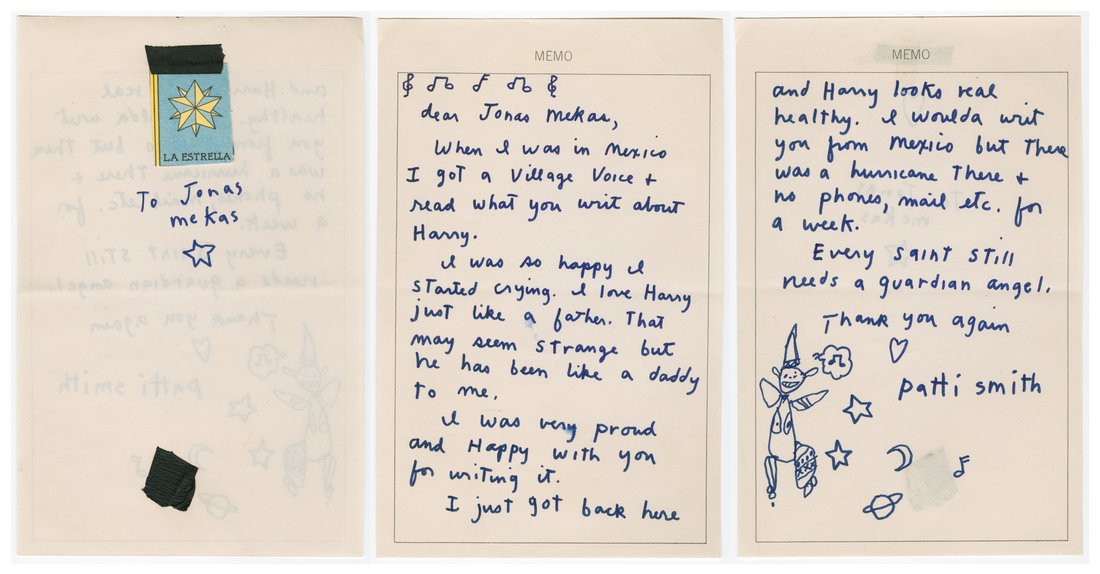

As they were settling into their new apartment just across the Williamsburg bridge and were repainting it, they listened to the recording of Irving Berlin’s song How Deep is the Ocean performed by Peggy Lee and Benny Goodman’s jazz orchestra. “How far would I travel, to be where you are?” one of the lines said, and it must have been a touching conclusion after so much that they’ve been through during this chapter of their lives. People were reminded of this story by another old friend of Jonas, Patti Smith, at the tribute event on February 21 this year, where she gave her own rendering of this musical gem.

Sebastian also told me that in terms of classical music, his father was very much influenced by the taste of George Mačiūnas, who was tremendously well versed in the history of music literature – especially early music. He was not so much fond of Mozart or Mahler; he would have rather chosen Pergolesi and was a huge fan of Monteverdi. Before he died, George was saying that he would have loved to have seen the lost operas by him – he was expecting to do that in the afterlife. Some of that music – like the madrigals of Monteverdi – landed in the background of Jonas’ work. George also introduced him to the musical endeavours of Ezra Pound, better known as a poet, notably his opera Le Testament de Villon, written under the influence of the troubadour tradition.Jonas Mekas was involved with a lot of musical figures, who became critical to the musical landscapes of New York, and who set trends globally later on. There has been a lot of mingling in New York in the different arts: poetry, music, drama, cinema. Robert Frank, Philip Glass, La Monte Young, Allen Ginsberg, Barbara Rubin were just a few of those who were close to Jonas. Barbara Rubin, to whom the last edition of Film Culture is dedicated, connected many famous people: Bob Dylan, The Velvet Underground (their first performance was famously filmed by Jonas too), and many others.

And, of course, they were at the pinnacle of the musical avant-garde of the time in the 1960s, listening to the newest pieces by the leading artists both from New York and from Europe. In his note on January 2, 1965 he has very insightfully compared the music of Karlheinz Stockhausen to that of John Cage which he heard played by Max Neuhaus and James Tenney at the place called Y, which is still operating on 92nd as it was at the time:

“Stockhausen dramatizes the sounds, melodramatizes them. It’s still Wagner etc. It bothered me all evening, and I tried to understand why. The piece was masterfully executed and rich in sound etc. – But it bothered me, it seemed almost a misuse of sounds just as sounds, separated by pauses and placed in space with no dramatics. After the few moments of Cage everything became immediately clear. What a difference! Here we have pure sounds, or almost pure (execution sometimes seemed to dramatize them, but not enough to destroy the purity and nakedness of the sounds) – the beauty of sounds left in the world by themselves is enough to keep you in suspense, yes, almost in suspense, because of the tremendous tension created by silences, because of the tensions between the sounds and the listener. I never realized until this evening the greatness of Cage, the purity of Cage & how old-fashioned and impure and melodramatic Stockhausen is when compared with Cage!”[4] He added later that “It was an experience <…> equal only to La Monte Young’s Second Avenue concert that we went to with Andy [Warhol] four weeks ago: there, too I was sitting on the edge of the seat for two hours, and I wasn’t the same man when I left the place (or perhaps, more truly, I was awakened to myself, I was more myself).”[5]

There was another huge influence, not only to Jonas, but to many American musicians at the time – Harry Smith, who was a visual artist and a filmmaker, but was also responsible for a huge folk, blues and country music anthology he had compiled: digging up many obscure records, eighty-four in total, in small towns and villages in the American South, recorded originally between 1927 and 1933. Everybody from Bob Dylan to Beck was using them as their influence – it marked a kind of a revival of American music. This collection came out in 1952 under the title Anthology of American Folk Music, and since Jonas was very close to Harry Smith, as for many years they lived in the famous Chelsea Hotel next to each other, he was very much influenced by that collection. Films by Smith were shown along with the works of Jerry Jofen, Robert Whitman, Barbara Rubin, even Andy Warhol.

And Peter Kubelka, a longtime comrade filmmaker who was classically trained and a Vienna choir boy in his childhood, with a taste for avant-garde music as well. So, Harry Smith, Peter Kubelka and George Mačiūnas – these were the great influences at the time, and a lot of music that ended up in films was by them.

As one listens to the music in the background of Jonas Mekas’ films, one can notice that it follows (or perhaps the contrary – doesn’t follow) his method. It is very free and open, the music does not necessarily overlap with what’s happening on the screen, sometimes it’s repeated later in the film, while occasionally he would choose something very particular – like his use of different preludes by Čiurlionis in his Reminiscences of a Journey to Lithuania. He believed that Čiurlionis’ music really captured something important for this work.

Another chapter started in the 90s up into the 2000s, a lot of different artists wanted to visit and meet Jonas, especially when it was finally possible – after the collapse of the Eastern bloc and the end of the Soviet Union, and it evolved into many long-lasting friendships. And so, in one of his letters addressed to his “Paris friends”, July 8, 2002, he writes:

“Ah, Music. Why didn’t I become a musician… This evening at Anthology I went down to the basement, Auguste [Varkalis] and Dalius [Naujokaitis-Naujo] were playing. But they were pretty drunk on vodka and I didn’t feel like vodka tonight, so I left. I bet they are still playing. Just for themselves. Dalius on drums, Auguste on his Charlie Parker sax. It’s 12:30 AM now. On the radio: a madrigal, very happy one.”So, wanting a little more insight into that time, I decided to meet those two characters – Dalius Naujokaitis-Naujo, of whom I had heard a lot before, and Auguste Varkalis, quite a mystery for me but, as it turns out, one of those who witnessed and participated in so many things around Jonas Mekas at the time. They both were active in the musical background around Jonas.

“Jonas had a really swingy rhythm inside – it was amazingly free and effortless. He was truly musical, perhaps because he grew up surrounded by singing”, Dalius told me. When we met, Dalius just bought a percussion instrument which belonged to the legendary Cecil Taylor and was working on the upcoming performance he and other friends of Jonas Mekas gave at Rupert, an arts space in Vilnius.

Dalius started off his career as a percussionist back in the late 80s in Lithuania, where he engaged in avant-garde jazz, free improvisation and wild experiments with many of the leading musicians in Lithuania – Vladimir Chekasin, Petras Vyšniauskas and Juozas Milašius among others. It is not surprising that he was drawn by the temptation to move to New York – the natural home of these musical fields. Throughout the years he became a native on the New York scene, playing at renowned places throughout the city, including Blue Note, Nublu, and The Stone (formerly in East Village), among others. The makeup of the bands he runs or plays in is constantly changing, but among his faithful companions on stage are Kenny Wollesen, notably with the band called Uzupis, Jonathon Haffner, Sean Francis Conway, Kirk Knuffke, Michael Formanek, and many more.

“He is not normal!”, Jonas Mekas used to say, often amazed by Dalius’ musical talent, “He is totally possessed by his art, nothing else matters to him! The muses of music have made him lose his mind, he is moving ahead unpredictably and dangerously, as all poets do.”[6] Their friendship started on the same night Dalius Naujokaitis-Naujo came to New York in 1995. His brother Audrius Naujokaitis, who was already there, knew Jonas quite well. On the night when Dalius came, Audrius called him to say that his brother had arrived. Jonas just said: “Let’s meet at McSorley’s.” The next morning, he wanted them to help him get the trash out from the Anthology. And so it began: they all went to the legendary Mars Bar, right across from the Anthology Film Archives (at present a branch of some bank) and started playing. Later Jonas had let him set up a studio in the basement of Anthology, and it became a place where many musical ideas originated and came into being – it lasted for about 12 years. Dalius remembers Jonas Mekas with the utmost admiration. “Jonas heard everything – Charlie Parker playing. Live. You know what I mean?” He got him and Auguste to the studio of the legendary Ornette Coleman, at 52nd Street, to listen to the rehearsals of his band as well. All of them, including Jonas, would come often to play at Anthology, just for themselves, not as at a concert. “Everything evolved by itself, someone joined, and we could go on like this forever – the energy was tremendous, everything was real, not pretentious, not that we posed ourselves as musicians. Everybody was welcome.”Auguste Varkalis is a painter who later took up musical improvisation, and himself tried moviemaking too. He often played in the Anthology Film Archives basement with Dalius. Auguste lived in New York for 11 years, eventually moving back to his native Kaunas, where he is based right now. “I don’t play so much anymore,” Auguste said. “Sometimes I still do something for films.” There was another story too, I heard details about it from Sebastian as well. In one of the benefit concerts at the Anthology Film Archives, there was a performance by Philip Glass. They had to move in a Steinway grand piano for his concert, and he would play in the background of a film on the screen. “Glass played wonderfully, the water was flowing, and it was a great match with his style. That's why he’s Glass – because he’s transparent.” According to Auguste, Philip Glass lived just across the street from where the Anthology is. After the performance, the piano was still there, and Auguste started improvising. These improvisations later turned into the soundtrack for Jonas’ important and very long film As I Was Moving Ahead Occasionally I Saw Brief Glimpses of Beauty.

Auguste himself, first known as Eugenijus Varkulevičius, was close to Justinas Mikutis, philosopher and mystic – a legendary figure within the Vilnius Art Institute (now Vilnius Academy of Arts), where Auguste studied painting. As Auguste left for Berlin in 1990, he saw the city during its most radical changes. He painted (on canvas) the Berlin wall that was being dissembled and spent his time among different political and artistic groups. They were friends with Audrius Naujokaitis, Dalius’ brother, who was already in New York and was planning an exhibition there. He invited Auguste for a visit. That’s how he decided to go there and ended up for 11 years with all the bohemian crowd which gathered around the figure of Jonas Mekas in New York.

Auguste was very much into the Fluxus movement at the time, got interested in Joseph Beuys and, of course, George Mačiūnas. The latter was the main reason why he wanted to meet with Jonas Mekas – he wanted to learn more about Mačiūnas. Auguste had relatives in Chicago, and, as he has put it, he was talked out of going there by Jonas. He started living in the room just behind the cinema screen at the Anthology, often he was asked to improvise for the silent films. He took up film himself as well, while his painting style changed more into an abstract one. At some point he had a correspondence with Stan Brakhage and attempted to use acrylic paint on 16mm film – he wanted to transpose his abstractions into the moving image.The Anthology has seen many of Jonas’ friends playing – among those were Patti Smith, Laurie Anderson, Philip Glass, John Zorn, Sonic Youth (who would frequent Tompkins square in East Village as well), The Velvet Underground and Lou Reed. Dalius and Auguste got a chance to meet them, while also spending time at the Anthology Film Archives.

On the New Year’s Eve, it was common to play in the lobby of the Anthology, and Jonas used to bring his trumpet and start the magic. Eventually, they formed another group, called 2nd Avenue, 2nd Street, and they had almost convinced Ornette Coleman to join them for a project, although in the end, that didn’t happen.

According to Dalius, Jonas could play on anything – be it a fork or a drum set. Some of the jam sessions they had at the basement have become releases. They ended up at a bar called Zebulon and performed there for many years. That’s when Dalius started playing with Kenny Wollesen, another friend of Jonas. Zebulon became their favourite spot; they would come there, grab a beer and join the performance one after another. For a year or so they played there every week. The place was around until 2013, and later it moved to Los Angeles.

Out of these concerts at Zebulon, a group called Now We Are Here emerged. They played at various galleries, with John Zorn at The Stone, Nublu, and even went on tours to Europe. Among other things, one can listen to some of the recordings on his still very active website, under the music section. The Summers of New York is my favourite.

It is extremely hot again in New York, presumably like in the summer of 1948, when E. B. White was writing his essay – now, in August, the airshaft hovers above me, and my mind is almost melting at 90 degrees Fahrenheit (over 32 in Celsius). “New York blends the gift of privacy with the excitement of participation,” wrote E. B. White.[7] Once in a talk with Jonas Mekas, Susan Sontag complained that Europe offers much more exchange than New York – “writers, artists, intellectuals, they all meet each other, you meet them naturally”[8], to which Jonas replied that the “equivalent of that atmosphere you find here in the underground where there is the same kind of exchange.” It seems that Jonas was and still is the crucial element to feel that spirit, with the underground for some becoming their life experience, and one must be ready to dive in for it. This excitement of participation is one of the things which could describe who Jonas was, be it music, poetry or film. This gift of joy is what we will carry with us, all of us who had a glimpse into his life.

English text edited by Romas Kinka

[1] Mekas, Jonas. I Had Nowhere to Go. New York: Spector books, 2017, p. 293.

[2] Ibid., p. 10.

[3] Mekas, Jonas. Scrapbook of the Sixties: Writings 1954–2010. New York: Spector Books, 2015, p. 9.

[4] Ibid., p. 46.

[5] Ibid.

[6] jonasmekas.com

[7] White, E. B. Here is New York. New York: Harper and Brothers, 1949, p. 13.

[8] Scrapbook of the Sixties, p. 222.