Algirdas Martinaitis: “This music used to hurl me away unexpectedly, but this was just what I needed”

- Feb. 18, 2022

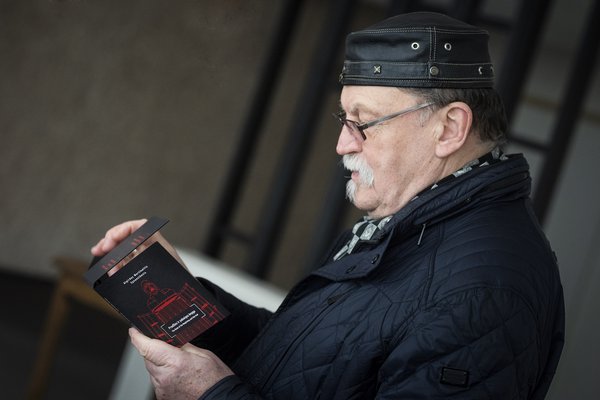

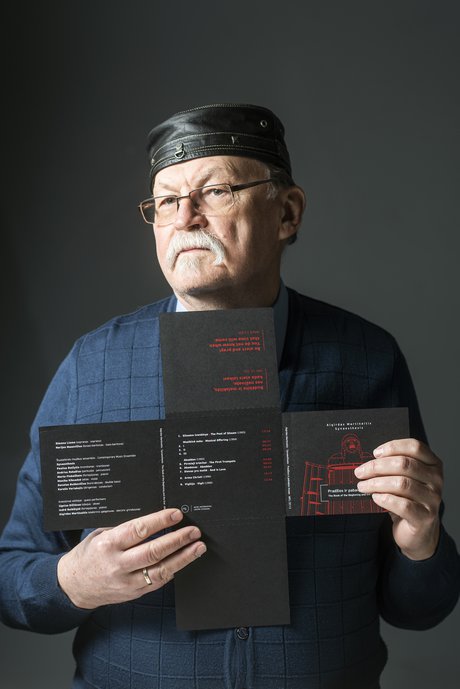

The Music Information Centre Lithuania has released Pradžios ir pabaigos knyga (The Book of the Beginning and the End), the new compact disc dedicated to composer Algirdas Martinaitis. The album contains some of his music written between 1993 and 1996 performed by the Synaesthesis Ensemble, singers Simona Liamo and Nerijus Masevičius, pianist Indrė Baikštytė, and oboist Ugnius Dičiūnas. The five titles – Siloamo tvenkinys (The Pool of Siloam), Muzikinė auka (Musical Offering), Abaddon, Arma Christi, and Vigilija (Vigil) – reflect the profound shift in composer’s worldview due to dramatic events in his life which have made him choose the path of a devoted and pious Christian. This music bears the motives of apocalyptic doom, repentance, humility, and compassion.

The album, sponsored by the Lithuanian Council for Culture, features innovative design, comprehensive texts, and the QR code for those who wish to listen online. Following the release, the composer spoke with musicologist Jūratė Katinaitė.

Conversations with you always dwell long in my memory. Each interview reveals several ideas that stay and even alter my worldview a little. Now we have met to celebrate the album of your music composed during the first decade of Lithuania’s regained independence. Several weeks ago, Ondine released a yet another album of your music, this time more recent. Everything is fine, yet I recall the first wave of the pandemic that ruined the events scheduled for your 70th birthday. Strict quarantine, as the finger of God, instead of celebration. What was your reaction?

After it has descended on us, I started wondering – what was it all about? Has the humanity experienced something similar? And how has art reflected on it? I quickly found The Plague by Albert Camus and started searching for similarities. All the earthly cataclysms are similar to something else. While on the Island of Patmos, Saint John looked at the stars and felt the Apocalypse together with the clouds and the universe. When we read it, we consider his story as a mere description of his feelings, yet it reflects the deep-rooted ties between a human and the earth. They reveal the birth of one thing from another and lead somewhere. The same might be traced in arts, irrespective of whether we speak of signs inscribed by primitive humans on cave walls or a symphony by Shostakovich. During student years, we did not like Shostakovich and Prokofiev. The different turn in music was all we cared about back then. Whenever I listen to Shostakovich now, I realise the grandeur of his writing, the clearest and most precise reflection of the society of the day. I could not possibly imagine my attitude would ever change in such a profound way. Listening to Shostakovich or Prokofiev now, I hear history.

It is perhaps wrong to state it openly, but, as it appears, you, together with Onutė Narbutaitė and Mindaugas Urbaitis, now represent the oldest generation of Lithuanian composers and therefore have to assume the burden of moral authority. Bronius Kutavičius has passed away, Osvaldas Balakauskas has ceased to compose after uttering his credo and spiritus, your peers Vidmantas Bartulis and Faustas Latėnas have burned out torch-like. The younger composers now will see you as their leading father and look at your back, offering shelter and safety, because it is you who fight the storms and no longer argue with them. You simply go on.

The generation before us has become the great names in Lithuanian culture. They served us as a protective wall many years ago. Daring and innovative, they offered us the new backgrounds in music, painting, and literature. The wall that was safe to stay behind while becoming of age. And suddenly the wall collapsed…

Now it is you whom others might consider the wall.

Here’s when I start pondering: What kind of life I live? What kind of music I write? I think I know and feel the young generation, because they possess the qualities that we had when we were young, the desire to resist, the wish to safeguard our individuality. The time will come when they start representing the nation. I feel their strength.

But don’t you feel resistance? The young people come and push aside what had been created, because they want to enforce their findings. The generational conflict has been programmed by the nature. There’s no other way. Or is there? Do you possess the courage to declare you trust in young people, although they might negate your own credo?

At the time when I was younger and yet there was already a generation younger than me, I lived in a village house and had rubber boots. I kept them at my bed and wore them every time I needed to get outside. Sometimes in the evening, I would get so angry after situations like some younger colleagues mocked at me, or whatever. So I would grab a piece of paper, write my feelings down and keep the notes inside the boots. A couple of days on, I would read them and wonder just how stupid I was to even care. I would then burn the notes. And this is what I think about taking small everyday offences. I used to burn the notes not because of what had been said about me, but because of my feelings about the insults. Those people, it was obvious to me, behaved like this just because they believed in what they did.

I am curious about the young composers’ music. I open their scores, because they reveal a completely different world. Their life is different as well as what they experience. Many of them live abroad, exposed to diverse influences. The changes in their music are natural, they are not directed against the older generation. I used to look at the more senior composers’ scores too and I have learned a lot. The First and Second Symphony by Osvaldas Balakauskas, just like the Third Symphony by Feliksas Bajoras, they resemble properly-sealed documents.

Let’s move closer to the new album, Pradžios ir pabaigos knyga. It contains your music written during the first decade of regained independence, the period that many now are keen to recall and reflect on. The times were tough as the Singing Revolution was followed by a “hard landing” which led to massive unemployment, acute shortage of basic products, the uncontrolled rise of criminal activity, the significant fall in theatre and music attendance. These were the phenomena many artists failed to adapt to. The limited yet stable and safe, at least in part, artistic field ceased to exist pushing the artists into a rather aggressive environment of capitalism. This album reflects your artistic response to the changes. From the broader perspective, the pieces recorded here should not be considered your typical music or, to put it more correctly, you have not come back to the same style ever since. Your early music, now considered your classics, is imbued with neoromantic worldview, while your later pieces are bigger and more monumental. The compositions on this compact disc, however, resemble mental sketches and experiments with new forms, sometimes marked with hurt feelings, sarcasm or anger. They all are very subtle and vulnerable, though. What was your mood back then? How do you see now these times and yourself back then?

Changes were all around. I moved out of the city to settle down in a village. I worked hard on my farm to make ends meet, including sowing and pig feeding. In the beginning, I even had my bed in a cattle shed. It was neat and clean, though. I was busy writing Siloamo tvenkinys (The Pool of Siloam) then, the piece about a blind man who sees the light after rubbing mud into his eyes. There were a number of springs around my place, so, coincidentally, I had my own “healing mud”. I wrote quite an undefined music for piano where, by the end of it, you become blind and, pencil in hand, are compelled to search for a piano key as if it were your way out. Such were the coincidences in my life. For many artists, though, a coincidence is something to be evaded or ignored.

Later I returned to city life and started writing Abaddon. Abaddon is the angel of the abyss. So, I returned to creative life from my abyss. Then the entire set of compositions was born – unplanned and mostly by chance, I have to admit. All of the music, however, is related to the New Testament.

Apparently, it was that period of spiritual and physical change that has forged the present-day Martinaitis who adheres to his steadfast values – the time of the young Martinaitis becoming the mature one.

My work for theatre was very important too, including my collaboration with director Jonas Vaitkus who has staged Forefather’s Eve by Adam Mickiewicz and The Father by August Strindberg. The music was initially intended for theatre, but eventually it became part of my string quartet Mirtis ir mergelė (Death and the Maiden). I have been in close contact with the Bernardine Church in Vilnius since 1994. I have written plenty of sacred music, especially after the texts by St Francis of Assisi. The time, just like the music composed during that period, was remarkably diverse.

It was then that you had to cope with the terrible shock after the street assault against your son who ended up badly injured. Was it the threshold that you had to cross before becoming a pious and humble Christian?

I was working on my Unfinished Symphony that summer, contemplating different subjects and experiences of my past. The premiere was scheduled for September, the month my son was nearly murdered. I wanted to end the symphony with the ascending motive as if illustrating a human leaving this world and dissolving. One member of the orchestra refused to play it. As if getting ready for the assault, my son attended a gym then, and this was what rescued him from death. Then I composed a different ending for the symphony. For me, everything that preceded and followed that horrible incident eventually turned into a chain of causes and consequences.

The music recorded on this album used to hurl me away unexpectedly, but, as it would soon become evident, this was just what I needed.

Sarcasm is an important and persisting form of your self-expression. Earlier, I was sure it had emerged as a defensive reaction to the changes, the “wild capitalism” and the chilling contrasts between the being and the daily routine. But the more I listen to your music of that time and the experience you articulate in words, the better is my understanding that the Christian humility lays behind it, as if because of feeling guilt for assuming the role of a creator and, consequently, becoming afraid of your own haughtiness, which leads to ridiculing yourself and your artistic efforts. In your words, you “cut the height of the piece to make it not that tall”. Is this an appropriate way to interpret your sarcasm?

Yes, definitely. Theatre has helped me to discover the ways of depicting sarcasm. In theatre, music serves in creating so many mental conditions. This has prompted my interest in the many forms of stupidity and idiotism. Soon I discovered that music offered plenty of deviations, or should I call them byways, that take you to completely different locations. My theatre experience has added all this to my musical vocabulary. Now I feel free to utilise the new opportunities.

I make plenty of drafts while composing a piece. A rough copy is usually followed by a second and third draft and only then a fair copy is produced. The evolution of music usually reveals the real stupidity of the initial idea which, through several drafts, cleanses itself to uncover art. I like watching the entire process by going through my draft copies.

Is it easy for you to let go with your music when it finally ends up in the hands of a performer, after all the drafting? Do you feel relieved then or perhaps still sense the urge to improve it?

Sometimes, when I open the score of an old piece, I notice that the idea was fine, but eventually I somehow went astray. I add some new touches now, because I feel that I had taken certain things wrong, often due to rushed work. I have been going through my oeuvre recently, and there is very little order in it. Many pieces appear in a number of variants and sometimes it is difficult to determine, which of them is my true son.

Did you need to edit the pieces for this album as you got back to them after such a long time?

In some instances, I had to re-assemble them from my old scraps. I have rejected some music altogether, Du liudytojai (Two Witnesses) being one example, as the piece originally involved a certain visual action. Without it, the music should be written differently, which would make it a new composition. Some music, on the other hand, was born as a revelation. After completing Vigilija, I realised I had no clue just how it had happened – as if entirely without my conscious effort.

Do you consider the perception of your thinking by the audience important? The majority of music on this album is instrumental, yet you articulate their ideas distinctly by naming biblical motives or, in other words, their subject matter. The listener, however, might design his or her own subject matters.

I am always curious as to how the audience perceive music. You know your own piece and all of your inputs, therefore you feel certain it should not reveal any new things. But every interpretation, it appears, opens up more opportunities than the composer was able to imagine. It is very much like Holy Scripture which could appear in four variants. I feel intrigued whenever I read about my music, because sometimes people notice the details that had evaded my attention.

What was your relationship like with the young generation of performers who recorded this album? Some of them were born at the time when this music was written. Were you able to communicate properly? Or have they perhaps found their own keys to your music?

Unfortunately, I often felt unwell during the recording sessions, which made my life quite tough. The musicians would call me to arrange the rehearsals, but often I was not able to attend. They would call me later and I would tell them I had another problem. Eventually they worked almost entirely on their own, without any significant input from me. Once, conductor Karolis Variakojis called me right before the rehearsal to ask about the tempo in Abaddon. I told him the following: “The metronome in 1996 was different from the metronome nowadays.” This music makes me both passionate and irritable as it bears so much of the old-time testimonies. It is fine with me they have performed it the way they considered appropriate.

To round it up, I would like you to make a prophecy. Artists always have a better understanding of where the things are heading to. We live in turbulent times. It is difficult to imagine the near future of the socio-political life. What will happen to music?

Plenty of music, art and churches have been created. Will people still need it? Or will it perish? Recently we have witnessed a sudden rush of interest in technology. Our food, on the other hand, has changed considerably too. We’ve stopped consuming the real food choosing the constructed products instead, their labels providing plenty of numbers. For me, those digits are closely linked to digital music and space. We are fond of the sound of a violin or any other instrument filling a space, yet a young individual wants more, he wishes to expand this space. This leads to the entirely different parameters of music. Whenever I listen to music by Arturas Bumšteinas, I feel he truly believes in the new models. I find his theatre music interesting. That’s another reality of music.

The new Lithuanian music, on the other hand, is written by so many young female composers: Žibuoklė Martinaitytė, Egidija Medekšaitė, Justė Janulytė, Rūta Vitkauskaitė... Earlier, writing music was considered a man’s job, but now women do it too, and this is something I find amazing! Women’s calling is to give birth to the world, and now they write great music too! I am utterly charmed with this.

Album The Book of the Beginning and the End is now available on Bandcamp and online store at MusicLithuania.com. The album have been financed by the Lithuanian Council for Culture and Lithuanian Ministry of Culture.