Domininkas KUNČINAS / Ore.lt | Military Infrastructure in the Battle Against Pop Culture

Music inside former military bases

Muses are silent when arms speak, they say. But even in wartime, artistic life may serve both as therapy and a weapon. Katerina, the Nightingale of Mariupol, who recorded a song inside the besieged Azovstal steel plant, has gained fame the world over. No one could have imagined Bono and The Edge performing at a Kyiv underground station turned shelter. But while the U2 frontman is safe and at home, Katerina, also known as Ptashka, or Birdy, has been captured by the Russian troops and released just after four months of imprisonment. “I’d rather die in battle than live enslaved,” she sang. Similar themes were popular among Lithuanian rebels who for several years fought against the Russian occupiers after the Second World War. They, like Ukrainians now, expected the West would support them, the difference being that the Lithuanians’ hopes never materialised. What they were left with was songs they sang in their dug-out bunkers.

There are a number of former military sites turned cultural spaces, including Bunkr Parukářka in Prague, Metelkova in Ljubljana, The Shelter in Beijing, and the so-called B018 in Liban, also known as Beirut’s Berghain. The Fusion Festival takes place at a former military airfield in northeastern Germany, while the famous Freetown Christiania in Copenhagen has replaced the abandoned military base. In Ukraine, many Soviet-era bomb shelters were used by businesses, from tattoo parlours to striptease clubs, before Russia’s invasion of the country. Now many of them are needed again to protect people.

Lithuania has seen many armies temporarily capturing its territory. They have left a lot of diverse military infrastructure belonging to various historic periods, from forts in Kaunas built by tsarist Russia and artillery defences along the Baltic shores erected by Nazi Germany to Soviet-era military bases and hundreds of shelters serving different purposes. After the end of the Cold War, the shelters built for civilian use became redundant. There were more than 300 of them in Vilnius alone. These abandoned premises appeared to offer ideal homes to underground subcultures, their rough interiors fitting the harsh and rebellious music, the concrete walls protecting the outside world from the noise. Between 1996 and 2007, former bomb shelters housed several music clubs in Vilnius, such as Bombiakas (Bomby), Virpesys (Oscillation), Gravity, and Vault. Just outside the city, fans would gather to dance in former missile hangars and at the Rocketshop raves. Inside the many forts of Kaunas, including the refurbished venue called Parakas (Gunpowder), dance parties are still a common occurrence. Inside Memel-Nord, the former artillery bastion in Klaipėda, DJs used turntables to call in friends of explosive rhythms, not guns to fend off the enemy. Just before the pandemic, Mars Fest was held inside the so-called Brezhnev’s Bunker in the provincial town of Kazlų Rūda.

Bombiakas, a refuge for punk rock

It was sometime during the 1980s that punks discovered an abandoned bomb shelter built in 1956 in Antakalnis, not far from the centre of Vilnius. Featuring two entrances, two ventilation shafts, three main rooms with ceilings 220 cm high, and several technical areas, it was designed in Moscow to house up to 150 people according to the initial plan. It has never served its purpose though. Just five years after its construction, the shelter’s “entrances were buried under waste, the inside was used as a public toilet. The filtration equipment was gone, like the two hermetic entrance doors,” the 1961 inspection papers say.

Punk rock is often associated with leftist ideas, but in Lithuania most of the punks were initially patriotic ultra-right nationalists due to the historic context. Untypically enough, local authorities, Soviet in essence yet pro-Lithuanian in important nuances, did not treat the punks harshly, which led, at least in part, to the thriving of the punk rock scene – and funny episodes such as when a KGB agent had to buy a ticket to enter a punk rock festival. It was the punks in Lithuania who opened their first club earlier than the devotees of any other subculture.

In the beginning, Bombiakas served as a rehearsal area for several punk rock bands, including S.K.A.T, Punktas (Point), and Erkė Maiše (Tick in a Sack). By 1996, however, the shelter was already a fully fledged club of underground music equipped and maintained by the local punks. Interestingly, they shared it with the aficionados of other music styles, including heavy metal, gothic rock and even fans of Depeche Mode.

The club operated illegally at first and was frequented by police, who once arrested all of the participants of a party. This led to the official registration of the venue by Mindaugas Savičenko, the frontman of S.K.A.T, and several of his friends in 1996. The former bomb shelter became Mūsų Kelias, a youth club named after My Way, a song by Frank Sinatra and also sung by Sid Vicious, the bassist of the Sex Pistols. On paper, the club focussed on offering youngsters leisure activities in several areas, including the arts, science, animal care, environmental protection, publishing, and drug awareness. It took some 300 signatures from the club’s members for the venue to receive official permission to operate, its water, electricity and heating bills covered by the municipality.

Four years on, in 2000, the managers of the club offered some insights to the then mayor of Vilnius, Rolandas Paksas, on how drug abuse should be tackled. Gyvenimas (Life), a supplement of one of the national newspapers, carried an article about the mayor who, during a visit to Bombiakas, the city’s sole club for what was then termed “informal youth”, discussed the problem of drug use in public places with the club’s leaders. Bombiakas, according to the mayor, “is known as a strictly drug-free venue, the managers of which know how to deal with the problem”.

The club has seen many more-or-less known domestic bands dedicated to punk and other underground music, including Dr. Green, Skylė (The Hole), Requiem, Tai Ką? (So What?), Turboreanimacija, Toro Bravo, etc. The relatively small venue was always full. Turboreanimacija, a legendary Lithuanian punk and hardcore band, chose Bombiakas for their farewell performance in 1998.

Apart from music, the club hosted a number of other initiatives, from flea markets to billiards competitions, and even published a newsletter, Bombiakas News. In 1998 and 1999, it spearheaded a social action against AIDS, which included discussions and a fundraising event to collect money for the commemoration of the club’s members who had died from overdosing. Several years later, the municipality cancelled its financial aid to the club, which coincided with dwindling visitor numbers. As debts mounted, the owners of the club sold it in around 2005 for a symbolic one litas, the then national currency of Lithuania, to the leaders of the gothic movement who soon proved unable to revive the venue. The club then closed its doors forever.

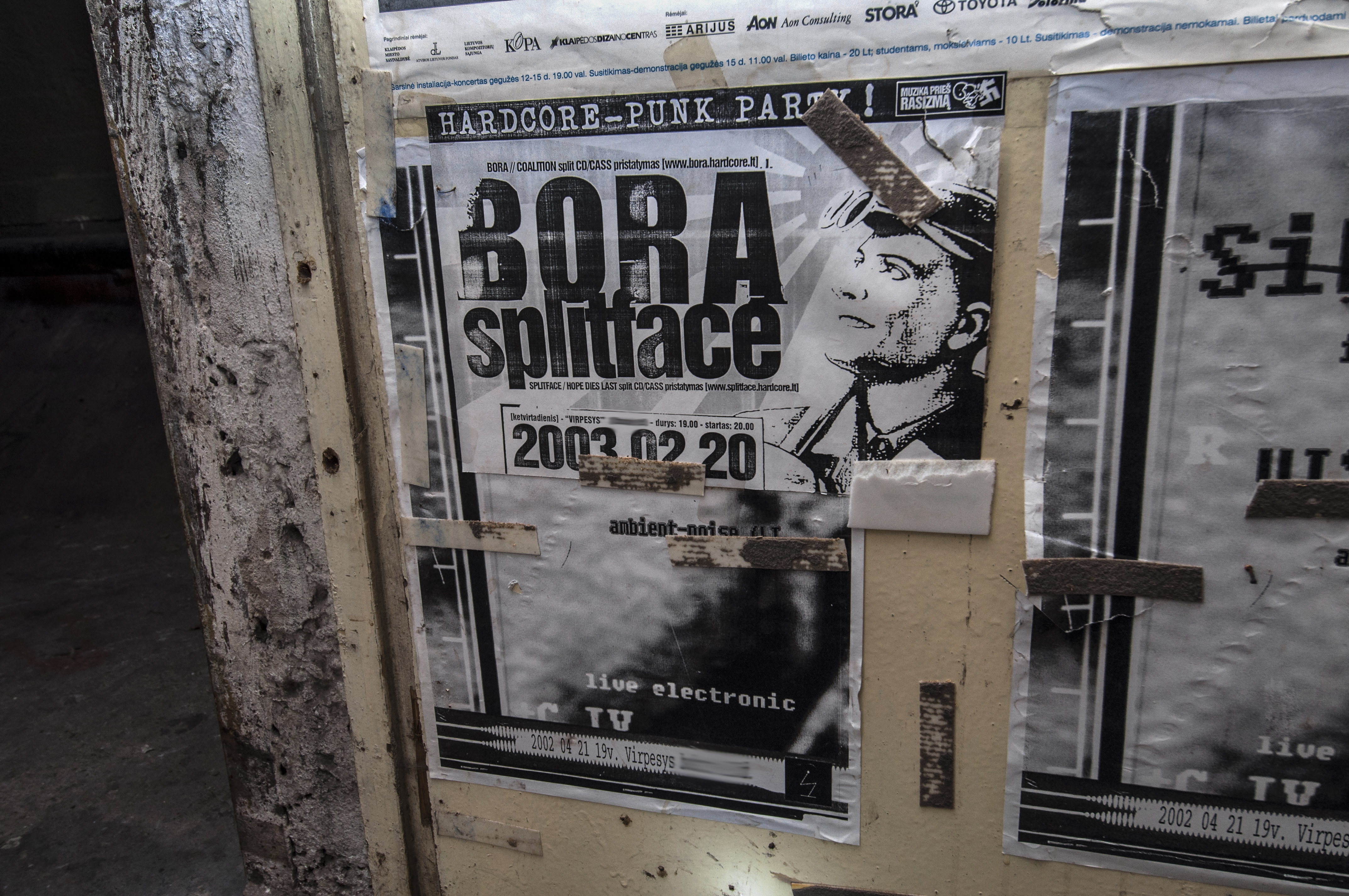

Virpesys hosts auditions of silence

Looking at a new parking area inside a courtyard in the Old Town, it’s hard to believe there’s an old bomb shelter under the fresh asphalt which two decades ago was a home for Virpesys (Oscillation), a club for lovers of uncommercial music. It was launched at the end of 2003 by a few friends eager to promote alternative electronic music. Although the venue lasted just three years, the music dwelled there much longer as the premises were used for rehearsals by several local bands, including InCulto, Lithuania’s choice for the 2010 Eurovision Song Contest.

The three founders of Virpesys, Gediminas Ušackas-Zuikis, Denisas Šafovalas and Vitalijus Kuzkinas, won in 2003 a tender launched by the Vilnius municipality to rent the premises. The place was totally dilapidated, yet the friends were bursting with enthusiasm to renovate it, something Gediminas would not even dare to consider nowadays.

“We cleaned the place up by removing heaps of rubbish, with our own hands, including several containers with strange liquids,” Gediminas recalls with a smile. “We made jokes about these being radioactive and that this is why I have no hair now.”

With the help of other like-minded buddies, they refurbished the area club-style – kind of. Despite its very basic interior, Virpesys was loved by its fans. “Why does anyone need all these nasty clubs playing techno and house?” one of the partygoers asked back then. “The interior? I have no problem with it! I love it.”

At the turn of the 21st century, Vilnius was famous for its thriving punk rock scene, its two main venues being the aforementioned Bombiakas and the GreenClub launched several years later. In the search for its niche, Virpesys saw its mission in bringing together the enthusiasts of underground electronic music, which often risks crossing the boundary of what is termed the art of sound. On some occasions, people would sit listening to an album of recorded silence. In other instances, the club would be filled with sounds not so much thought-provoking as appealing to a wider audience. The name of the club derives from the word “oscillate”, but the owners wanted it in Lithuanian. According to an unofficial version, the name was meant to remind the visitors of the draughts at the entrance that made everybody shiver.

One of the managers still remembers the opening night that brought together the whole of “alternative Vilnius”. The area, designed by the Soviets for up to 150 people, accommodated at least double that in an evident breach of all conceivable sanitary and fire protection requirements. Later, the club would often attract police who wanted the hosts to turn down the music, the low frequencies of which disturbed the local residents at night. The opening party included a performance of Ir Visa Tai Kas Yra Gražu Yra Gražu (And All That is Beautiful is Beautiful), a legendary avant-garde band led by its extravagant frontman, Artūras Barysas-Baras, who hallowed the stage in his own peculiar way by defecating there.

While running their own events and visiting similar venues abroad, the managers of Virpesys soon realised that the number of people interested in this type of music was very limited both in Lithuania and the rest of the world. Knowing there were almost no clubs dedicated solely to this area of subculture, they added techno and punk rock to their menu.

Despite its official registration as a company, most of the club’s commercial dealings belonged to the so-called grey zone, which was the only way it could survive. On the other hand, a considerable share of the national economy was semi-illegal back then, including all other underground clubs.

“At the time, we were petty rascals running an illegal bar,” Gediminas recalls. “Every time the police dropped by, we hid it quickly. Visitors paid us an entrance fee that was so small it could not possibly cover even the rent. Usually, we added money from our own pockets as we never had any profits from the club.”

The acoustics inside the concrete room were good and bad at the same time, according to Gediminas. “As a solid construction, concrete is better than, say, a metal hangar where it’s impossible to fix anything. As far as sound reflection is concerned, our visitors helped by absorbing some of it. We focused on alternative electronic music that is very precise, something we could enjoy fully at home. Listening to the music you love at the club was an achievement in itself and this is why we didn’t consider sound quality among the top priorities.”

The glittery underground of Gravity

Gravity, a dance club in Vilnius, opened its doors in December 2001 inside the former nuclear shelter of a Soviet-era shoe factory. Despite its slightly unfavourable location next to one of the main transport arteries of the city, the venue soon became a key component of the nation’s club culture. For several years in a row it was named Lithuania’s best club by the then influential online platform, ore.lt. During the ten years of its existence, it hosted more than one thousand parties featuring hundreds of bands and DJs from abroad and attracting an estimated 350,000-strong total audience.

Despite the fact that the country’s first dance-music clubs, such as Eldorado and Nasa, were launched back in 1994, it was Gravity that brought a real breakthrough into Lithuanian clubbing vogue. Gravity soon established itself as the city’s first western-style nightclub with a state-of-the-art sound system and what then seemed to be a forbiddingly high entrance fee, up to five times bigger than in most less-popular venues. It was Gravity that propelled dance music to the level of a legal business and spurred the emergence of other similar nightclubs.

“We found the premises in 2000,” said Daumantas Kairys, the then press representative of the club. “The area, one of many former bomb shelters in Vilnius, was completely neglected, its floor under water, its water and ventilation systems dysfunctional.”

Plazma, the architecture bureau that designed the venue’s strict-form interior, is still proud of its concept that converted the Soviet-era fallout shelter into a nightclub easily adaptable to diverse party concepts.

Once inside, the clubbers found themselves at the beginning of the 60-metre-long tunnel leading to a heavy entrance door, the only surviving original evidence of the bomb shelter.

Gravity was the nation’s sole nightclub to enjoy reviews by foreign media. Here’s how the Rough Guide described the place: “Ultra-cool joint dedicated to the best in cutting-edge dance culture. Attracts the best of the big-star Djs.” In 2010, Gravity made it into DJ Magazine’s list of the world’s 100 best nightclubs.

From its very first days, the club introduced a strict face control policy, a relative novelty in Lithuania back then. No wonder that finding a way in was a matter of prestige and inventiveness, at least during the first months after Gravity’s inauguration. Juozas, a well-known character among local bikers, worked as head of security. He, like his counterpart Sven Marquardt at Berlin’s Berghain, soon became a legend of the city’s nightlife and a man with whom so many craved to befriend.

Mahila, a Lithuanian blogger, posted in February 2013 a few lines of his reminiscence dedicated to the clubs of Vilnius that had ceased to exist, including Gravity. His post serves as a nice illustration of the club’s atmosphere. “Gravity. One might speak about the place for ten days and nights without pausing while sipping wine or downing spirits and sighing regularly for the good times gone. Grav, for sure, is an important chapter of Vilnius clubbing history as probably the nation’s best ever club boasting the most imposing list of DJs. And that incredible feeling when, after climbing the downward steps, you slowly pass the long corridor, your ears filling with the turbulent sounds that would draw you in and would not let go until the very end. The list of parties I attended is far from impressive and yet includes Deadbeat, Dieselboy, Darren Price, Carl Craig, Junior Boys, Robert Babicz, and the Nesakyk Mamai (Don’t Tell Your Mum) nights alongside many others I’ve already forgotten. Oh, how many bottles of Sobieski Vodka we drained while pre-partying in that car park nearby; how many GPLs [two shots of vodka and two of freshly squeezed orange juice] were gulped at the bar; how many conversations held in that amazing smoking area on the staircase; and how many mindblowing afterparties drifted to after Grav.”

The aforementioned originality of the premises and the distinctive minimalist interior helped the club earn its untarnished reputation and long-lasting popularity. Yet it was Gravity’s music programs that made it outstanding. Overall, clubbing life in Vilnius enjoyed a significant boost thanks to promoters from Europe who added quality. First off, it was Bernie Ter Braak from the Netherlands, who later launched Cozy, a club and bar in the oldest part of Vilnius. Several years on, he was followed by Rick Heffernan, an Irishman who came to Lithuania thanks to his friendship with Paul Murphy, a famous DJ who had previously performed in the city.

The list of producers, DJs and bands who have played at Gravity is impressive and would make any club of a similar size happy. It features James Zabiela, Ellen Allien, Goldie, Modeselektor, Fischerspooner, Ivan Smagghe, Kevin Saunderson, Simian Mobile Disco, Peaches, Junior Boys, Gilles Peterson, Steve Bug, Zoot Woman, Carl Craig, Datarock, Tiefschwarz, Adam Freeland, Adam F, Apparat, LTJ Bukem & MC Conrad, Mehdi, M.A.N.D.Y., London Elektricity, James Holden, Rank 1, New Young Pony Club and other big names in the wide realm of electronic music.

The club eventually closed in 2011, leaving distinct footprints in the history of Lithuanian music. Several attempts to revive the place have proven unsuccessful.

Vault, a hiding place for extreme music

Less than one year after the inaugural party at Gravity, the underground came out with its counter-proposal in the form of Vault, a club dedicated to extreme and uncommercial electronic dance music far from the glossy lights of Vilnius downtown.

Metro was the title of its debut show launched at the end of 2002 and featuring Grovskopa, a techno DJ and producer from Sweden. Located in a former bunker, Vault soon gained fame as a true bastion of underground electronic music and the place where fans of drum‘n’bass, techno, hardcore, industrial, noise, trance, and other styles could find refuge from the daily routine. The club, inspired by Western European underground culture, was opened and managed by DJ Black Box, an advocate of hardcore and speedcore, and the drum‘n’bass DJ ST, aided by dozens of volunteers.

Speaking in pleasant shade on a sunny day, Žilvinas Degutis, or DJ ST, recalls his schooldays and the very first rave parties he organised back then, eventually leading to the opening of Vault, a natural extension of his interests and ideas. Unlike the owners of Bombiakas or Virpesys, his friends and he knew from the very beginning that they wanted a club inside a bomb shelter.

“We were looking westwards back then, at Berlin to be more precise,” he said. “We attended the Love Parade, visited the legendary Tresor in the former underground vault of a bank, several clubs inside an old fortress, and other similar places. Electronic music was a novelty back then, a kind of weapon in the fight against pop culture. For us, the abandoned military sites – derelict and forgotten – seemed just what we needed.”

Before launching Vault, Žilvinas and his friends raved in Bombiakas on several occasions, yet this venue inhabited by punks was not exactly what they were looking for. They also paid a visit to Virpesys, but the place was clearly not for dance music. They spent two years looking for the right premises and eventually signed a five-year lease deal with the Vilnius municipality.

Vault operated inside an unusual complex built in 1970 for two Soviet-era organisations, a fur factory and a construction bureau. The site was used as a garage and was meant to offer shelter to almost 400 of their employees. In addition to that, military drills were held there before the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991.

For Žilvinas and his peers, the site – far from the buzzing streets and offering an exotic interior – was a symbol of their wish to fend themselves and the clubbers off from the rest of the world by immersing them in the music they loved together. While cleaning this long-abandoned place, the club owners loaded six large trucks with refuse. They also needed to deal with what homeless people had left there, and what they had taken from there, including all of the electric installations and locks sold as scrap. The club also required new loos and power supply, which soon proved vulnerable to overloads that would abruptly throw the party into silence and darkness.

According to DJ ST, the primary task was to survive while doing what pleased them. Unlike in Virpesys, the new club’s bar operated openly and paid its taxes, something that would often push the entire enterprise into net losses to be covered by the owners.

“It’s a pity we had to stop after the first five years,” Žilvinas said, “at precisely the moment when our initial idea was gaining strength and required further development. If the club had run for ten or fifteen years it would have been a success. We knew the city needed a large place like ours. At weekends, our audience consisted of people coming from Vilnius and also other towns. Initially the club was meant to house around one thousand people but later the maximum capacity was reduced to eight hundred or so. By saying this I don't mean we enjoyed capacity audiences every weekend. I remember a show with just four clubbers attending. All in all, we had less than a dozen nights that I would call truly outstanding.”

Initially, the club introduced a regular program with Fridays dedicated to techno and Saturdays to drum‘n’bass. About six months on, Žilvinas and friends realised this was not exactly what their guests wanted, so the format changed and now one weekend was for lovers of techno and the next for those dying for drum‘n’bass. As rumours about the new venue spread, fans of other underground music styles also used the club for their raves. Despite that, the frequency of the shows gradually decreased and eventually the club would open just once in a month or on special occasions.

Before the last gathering in 2007, the managers of the place made public their understanding of its name. “The Anglo-Saxon meaning of the word ‘vault’ refers to an area separated from the outer world, a place where you can hide or something can be hidden. A sea of people who, for a short while, want to forget the sunshine and their usual lifestyle under 120 bpm and who perhaps, at least a little, are tired of the fresh air, drifting clouds, soft-singing birds, and faint chords played by street musicians, they all have their own stories reflecting the essence and importance of Vault. Each and every one of those who have crossed the threshold of this bunker over the five years of its existence has seen a different darkness and felt the naturally synthetic sound at 180 bmp or even double that and has heard this pulsing wall of over ten-kilowatt speakers and met similar souls seeking refuge from the mundane.”

Once, at around 7 am, somebody called DJ Black Box as he had just locked the club to go home, Žilvinas recalls. “I’m inside,” the caller said, “let me out!” DJ Black Box opened the entrance again. The clubber came out and told him: “I woke up and opened my eyes but it was pitch dark. I am dead, was my first thought. Then I started touching myself realising I still had senses, so probably I was still alive.” Then he had turned on the light on his mobile and realised he was still in the club, not in hell.

Vault introduced a set of rules all clubbers were expected to follow. Here’s an excerpt: “Have an open mind. That means, don’t judge others / Dress accordingly – no high heels or shoes with open toes (a cold floor is promised) / We support radical self-expression – feel free to dance naked and walk around showing off the best you’ve got / Go hard or go home.”

Žilvinas has never thought the former military site had any influence on the club’s programs, yet he is certain its legacy added to the overall atmosphere.

“Since underground culture is intrinsically rebellious,” he says, “it fits in well with places like this.”

After the closure of Vault, enthusiasts of underground music styles started gathering in other places. Vault, it has to be said, was far away from other key nightlife centres in Vilnius, distance-wise, a clear disadvantage for the club. It was subsequently used for several years by an independent theatre. Before leaving, the actors left several spectators inside, mannequins hanging on the walls. As gentrification in Vilnius has gained in strength, the area is no longer considered a godforsaken nook and is ready for major redevelopment.

In August 2021, the new owner of this former garage and bomb shelter said in a press release that the old structure would be destroyed to give way to a new residential complex. The developer offered the former managers of the club an opportunity for a final rave, a goodbye to what once was Vault. The idea brought together many of the club’s former residents, including the Techstylism team that was behind many of the parties held there. Other guests were Android, an admirer of heavy techno; the duet DJ ST and MC Strazdas; Haze, Drumm, Fantas and Nervas, all dedicated to drum‘n’bass; X-Ray, an unrelenting trooper of hardcore; and, of course, Black Box, the speedcorer and former owner of the place.

For Žilvinas, who has for years been working in the music and film business, Vault was a huge source of experience which eventually translated into the clear understanding that hard work always pays off. He still recalls the emotions of a number of DJs from Japan, Canada and the United States who were thrilled after first entering the club’s grim interior, which leaves few others unimpressed.

Rocketshop: illegal raving at rocket bases

“The event met all of the criteria attributable to the sweet-sounding term ‘illegal rave’. Its date changed, people had to find the venue by studying maps, and the rave took place at an abandoned military base, the source of power was a generator, and the music there was radical enough,” a witness of the first Rocketshop party wrote in the early 2000s.

For several years, rumours kept spreading in Vilnius and beyond about illegal dance parties held somewhere inside an abandoned missile launch base. A former Soviet military command centre was the new rave location, it eventually turned out.

In 1971, the Soviets upgraded the air defence of Vilnius by installing Vektor, a new automatic system that eliminated the so-called human factor from decision-making and was meant to give direct orders to anti-aircraft units. To operate the new system, a dedicated command centre was built in the forests in Visoriai, then in the outskirts of the capital. The 466th Rocket Launch Brigade, incidentally, operated in 1987 the S-300 long-range surface-to-air missiles currently used by Russia in its war against Ukraine.

Paulius Linčius, now a businessman dealing with solar energy, was known as DJ Moon Disco twenty years ago and was a member of the GoodWillPeople promoters’ band. Paulius, who has not quit as a DJ, recalls the first party he organised. “It took place in a café in Vilnius. Later we started playing in various bars and cellars. We were all different, so it led to a kind of mish-mash situation as one of us would play drum’n’bass, another would offer house, a third would mix in techno. But at the start of the 21st century we needed more clarity and this is why we started planning a techno-only rave. Somebody mentioned a bunker near Vilnius.”

The Soviet troops had long since left Lithuania, but the national army had taken over only some of the sites the Soviets had occupied. An abandoned rocket launch site was perfect for the vision of Rocketshop. Out of several hangars there, the organisers chose the smallest, as no one could be sure just how many people would turn up. The promotion campaign for the first Rocketshop consisted of five posters indicating the title and venue of the event, and word of mouth.

The new rave was launched by a joint team consisting of several enthusiasts of alternative dance music from Vilnius led by Paulius, Zuikis from Virpesys, and X-ray. They would organise several Rocketshops and one Manifest.

“I was guarding the entrance to the site as a watchman,” Linčius recalls. “The entrance fee was ten litas. Or fifteen. But that included a CD featuring a mix by DJ Hallucin. We had recorded a hundred of them and they were gone in no time. All types of characters wanted to get in, from ravers and criminals to prostitutes and businessmen. A total of three or perhaps four hundred people arrived at the place that night – wow, if you consider that we’d been used to several dozen dancers in bars and cellars. Me, I didn't see anything, sadly, as I controlled the entrance. We had, I suppose, two kilowatts of sound supported by an old three-kilowatt generator. It took three people to refill it with fuel. One kept the bouncing generator in place, the second held the funnel, the third made sure the muffler didn’t disconnect as it held on just one screw. The generator did the job, but the amplifier conked out and somebody had to rush home to bring his own as a replacement. A single strobe for lighting. And plenty of smoke. This was the first truly illegal rave. We arrived at the place, cut the lock, turned on the generator, had the party, and then disappeared.”

After the fall of the USSR, there were plenty of unused sites both in Vilnius and elsewhere. You could do whatever you liked there, paying nothing to nobody. Better still, these places required no maintenance and were often located far from any residential areas.

The second Rocketshop nearly collapsed, because the police and military showed up just before the rave and ordered everyone to leave. But somebody knew an alternative spot nearby, so the caravan of cars loaded up with the equipment moved there and the dance party went on ‘til sunrise. It’s quite possible that the ravers danced at the auxiliary site for the S-300PS missiles several kilometres away from the former command centre. Disturbed by the sound, local residents would call the police, but it was often difficult to locate the source of the music.

Yet another military site in Vilnius, an anti-aircraft base for S-75 and S-75M missiles in Burbiškės, became the venue of Manifest, a larger rave launched by the same team. Promotion-wise it was more sophisticated as its advertising campaign included a dedicated website and flyers. The organisers installed a sound system of up to 15 kilowatts and hired a private security firm. The party, however, proved a total disaster in financial terms, which is the main reason Paulius has never tried launching any other illegal raves since. Nowadays he prefers promoting regular club events and advising beginners. The feeling of responsibility and the audiences today, according to him, would make him consider a great deal more event-related aspects, many of which he simply neglected during the days of Rocketshop.

Despite that, Paulius, the faithful promoter of dance music in Lithuania, remembers times past with pleasure and some pride. In an interview with Kultūrnamis (Culture House), an online magazine, he said: “The current ravers, I guess, lack that kind of joy of discovery and anticipation of a party, the hunger to join it. Or perhaps they experience it only before certain big events that occur once a year. Earlier, the scope of options was incomparably smaller, and this is why we craved for each new party as passionately as a thirsty man wants a sip of water. We hunted for the flyers and, after the rave, lived with our memories for months on end. Nowadays the romantic feelings have reduced considerably, because people know they can have a party every weekend.”

The Holy Trinity of techno, drum’n’bass and hardcore constituted the essence of Rocketshop, Paulius says. For him, history went the full circle and currently he includes in his sets some techno music that other DJs used to play at Vault. DJ X-ray, another resident of Rocketshop, still keeps faith in hardcore and performs rarely yet resolutely.

Several years on, the leaders of Vault organised Rocked Launched (in 2007) and Raketos (Rockets; in 2008) instead of Rocketshop. They raised the entrance fee to 35 litas and invited DJs from the United Kingdom, France, and the Netherlands who played alongside the locals.

The black rave fortress in Klaipėda

In 1939, Nazi Germany started building coastal fortifications near the port city of Klaipėda. One of these, Memel Nord, consisted of two 86-metre-long artillery blocks and a bunker housing the fire control centre. Six decades on, its concrete walls welcomed One Ear Stereo, a DJ team in charge of what became known as the Nature Primitive Sounds rave nights combining a romantic beach of the Baltic Sea, the brutal and somewhat ominous military architecture, and modern dance music.

Eugenijus Konstantinovas now lives in Berlin and works as a sound designer for Bitwig, the company behind a digital audio station. In his native Lithuania he is often remembered by his former stage name Genys (Woodpecker) and for the parties he once organised in the bunker in Giruliai by the Baltic Sea. He revived the past several years ago by playing his footwork set at the once popular site.

“Latvians launched drum‘n’bass raves inside bunkers in Liepaja before us, something that made a big impression on me,” Genys recalls. “They offered the combination of the military venue, the sea waves crashing against the shore at night, the mighty stomach-turning bass, and the heavy drum‘n’bass enjoyed by a crowd of beautiful people, fine DJs, and proper management included. Before long, we’d made an attempt to arrange something similar in our bunker as well, something we had discussed and been aware of for quite some time. But the one thing we really needed to accomplish beforehand was cleaning up the place, which for many years had been used as a public lavatory. We brought the sound systems and installed the power generator on top of the bunker. We then connected it to the hardware inside and had to make sure it operated uninterrupted through the night.”

But face control eventually turned out to be the toughest task. “The level of interest in the party was huge,” he says. “In Klaipėda, everybody knew us, so the news about the new rave spread quickly even without any flyers. We made it a special event and banned plenty of hoodies from entering by telling them it was a private party. The bunker was jam-packed, with dozens of people also enjoying the party in the dunes and by the sea. The first event, I believe, attracted about three hundred people, including fellow ravers from all around Lithuania.”

In 2006, the bunker hosted a party launched by the Unsound Method Crew, yet another DJ team from Klaipėda who called their rave Misconception. Here’s what Ore.lt wrote about it at the time. “No monotony, no shitty consistency. Just as it should be. The speakers, alas, sometimes threw up more bass than necessary and then, due to the bunker’s low ceilings, the low-frequency sounds, stuck inside, turned the intestines over, the image desynchronised with the sound. A pure fuck-up, in a word. Half an hour inside that mincer and you needed to relax in the best possible chill-out zone, the beach, where the rumbling waves shrouded the roaring generator, where the dunes were the sofas, and where no one cared about bio-toilets.”

The year 2009 saw another mighty invasion of the bunker by ravers. Shoreward, the event dedicated to electronic music featured almost forty DJs playing all night long at seven different spots.

More recently, Simonas Gudelis took over the tradition launched by One Ear Stereo as he used the bunker for Spiritus Sanctus, a series of raves held between 2016 and 2018. The raving tradition in Klaipėda, according to him, has lived on since the very first parties in the 1990s with most gatherings arranged at untypical sites, such as boatyards, ferry slips, former tobacco factory and furniture plant, and underground parking spaces. Prior to each raving season, Simonas and friends had to work hard to clean up the bunker from both human-made waste and the sand washed in by the sea.

The seawater and sand has recently been taking over the site, part of which now finds itself on the beach. The main chunk of the remaining fortification still lies partly hidden by the dunes and houses an exhibition launched by history enthusiasts and the administration of the Seaside Regional Park. The display says nothing about the raves held there, yet some might be reminded of them while looking at the faded graffities.

Mars inside Brezhnev’s Bunker

Mantas Daugėla, a keen aficionado of electronic music from Marijampolė, a town 140 kilometres west of Vilnius, launched with his friends in 2018 the first Mars Fest at what was known as the Brezhnev Bunker. The site, named after one of the last leaders of the Soviet Union, hosted the second event the next year, offering two locations for the audience this time, one outside and the other underground, in the former cinema. The organisers also added more sound and light, new installations, and more performers who offered a greater selection of musical genres. The crew landing at the Red Planet included Moon Disco, a highly experienced pilot of Rocketshop.

The military site near the town of Kazlų Rūda had existed in the depth of the forests since 1975 as a base for the Soviet Army’s Seventh Special Force Division. The secret object consisting of more than fifty buildings and an airport with a 2250-metre-long runway was known among the military as the Kaunas Bridgehead. It also featured fuel storage, a villa for generals with a large dining room, a sauna with billiards and a small pool, and, sure enough, a command centre dubbed Brezhnev’s Bunker.

According to the reference book describing the principles of Lithuania’s administrative division in the Soviet era, “the covert underground command room (of 1,000 square metres) was 800 metres away from the villa; military barracks reminiscent of a barn were erected on an ordinary little hill; a long and narrow staircase led from there to the underground where the temperature was maintained the same in winter and in summer. The bunker, located ten metres below the surface, had all of the vital utilities installed including gas and water supply, sewerage and autonomous power generators, ventilation systems, and satellite communications. It also offered a living area for military specialists, primarily communication and encoding officers, and a dining room.”

The 1977 Soviet action film ‘In the Zone of Special Attention’ is about four paratroopers who, as part of an exercise, have to capture a secret command centre located inside this particular bunker near Kazlų Rūda.

It took quite some time to locate this legendary place, Mantas recalls. “We roamed the forests until dusk after arriving there for the first time, and we went home empty handed. We still had faith, though, and the next time brought with us a friend who had been in the bunker. Finally, we approached a private territory, surrounded by a fence. We talked to a guard there who gave us the owner’s number. As I had organised a number of raves at abandoned sites, I felt a personal urge to launch a party there. It took three years for me to negotiate the terms of the first Mars Fest, which took place on a leased section of the forest next to the bunker. Having gained the owner’s confidence, the next year I was lucky enough to lease the entire bunker for the second rave.”

Mantas and his team, like so many of his peers, had to do their best to make sure everything ran smoothly. The list of main challenges was determined by the bunker’s location, some three or four kilometres away from any civilisation and deep in the forest. These included clearing the road, fitting signposts, preparing a parking area, and fixing the ventilation inside the bunker, up to twelve metres beneath the surface of the ground. The power supply was among just a few key aspects posing no problem at all, since the former military site boasted all its power systems heavy duty and intact.

The first full-scale expedition to Mars Fest, in the summer of 2019, involved several hundred ravers.

This type of location, according to Mantas Daugėla, unquestionably offers a specific atmosphere, the site itself becoming a source of attraction. From the publicity point of view, the events held at such venues can easily be conceptualised. The “consumer”, on the other hand, is always niche, very specific and scarce, all this given that the same people usually have more than one option to choose from.

The fortifications of Kaunas

It was in 1879 that Alexander II, emperor of Russia, approved a plan from his military leadership to build a new fortress in Kaunas, the city at the confluence of Lithuania’s two main rivers, the Nemunas and the Neris. Strategically located, the new installation was meant to protect the important railway bridge and tunnel, key roads, etc. The construction of the polygonal structure in the city proper and its suburbs was inaugurated in 1882 and went on until 1915 when German troops occupied Lithuania. A total of nine new forts were erected, and another four were left unfinished. The modern defences were meant to withstand a 180-day siege, according to initial plans, but it took the Germans just eleven days to overwhelm the Russians in Kaunas. The defence system lost its importance after the First World War, its forts lying idle and empty for many years. It was much later that some of its parts became public venues, while later still, in the 2010s, the former forts started hosting dance parties.

4$HO, a team of enthusiasts dedicated to techno, house, acid, electro, and other styles, who were active in underground Kaunas between 2014 and 2016, organised their Kaleidoscope raves near the former gunpowder storage. The dance parties enjoyed great approval among fans, many of whom witnessed in 2016 the police ending the gatherings with the organisers eventually offering a new location inside one of the city’s pedestrian tunnels.

The aforementioned storage facility opened to the general public in 2018, becoming one of the few former military sites converted into a cultural venue. The main building, on the right bank of River Nemunas, was completed in 1894 as part of major reconstruction of the whole defence complex. Located inside the hill, the 500-square-metre structure features two entrances and a specific lighting system. In the late 1900s, people still used oil lamps to light the storage, but to protect the gunpowder from exploding the lamps were placed inside purpose-built recesses lined with mirrors.

In the wake of the First World War, the Lithuanian army took over the entire complex. In 1940 and after the Second World War, the Soviets took control of the fortress which remained neglected for many years after the restoration of independence in 1990. More recently, Kaunas municipality has launched a program to revive the site in cooperation with private organisations and a number of individual enthusiasts.

Baterija (Battery) was the name of the interdisciplinary festival of culture that took place at the former fortress soon after its opening as Parakas (Gunpowder), the arts centre. The event featured Brigitta Bödenauer, an Austrian artist known for her noise experiments, and a number of local aficionados of electronic music. Ghia, the organisers of progressive music shows, soon joined the festival by launching their Baterhia at the Third Fort and bringing together many of the best in Lithuanian alternative electronic music at the time, including Arkhad, Girnų Giesmės (Millstone Songs), Karkasas (Carcass), Obšrr, and Orchach. In 2019 it was Ghia again who announced Buitis (Chores), a huge event which, apart from the rest, featured two live bands – Pindrops from Vilnius and Molchat Doma (Mute at Home) from Minsk, Belarus, who have recently gained international fame.

Today, Parakas is a home for diverse music, from New York-based Timber Rattle to Clementine from Africa, from industrial culture to hip-hop “explosions”, and from blues to bikers’ brutal orchestras.

A representative of Ghia, Algirdas Šapoka, hints that during the long months of quarantine, a team of barely legal producers known as SNKB held dance parties on several occasions inside the former bunker of a machinery plant in Kaunas. That is about all we may ever know about them, as information about the events spread mostly by word-of-mouth back then, with mention of them on the internet deleted immediately after the rave.

In the wake of the pandemic, the promoters in Kaunas have revived gatherings inside some of the many former military installations their city has to offer. In the first half of summer 2022, for instance, they launched a nightime rave at the Kaunas fortress featuring breakcore, acidcore, industrial hardcore, drum’n’bass and the like. Signposts carried a warning to visitors: “Do not meander. Be careful within the territory, especially out in the forest. Explosives have been found, they can be dangerous after winter.”

According to Šapoka, most of the military and civil defence objects, such as bomb shelters built at the many key Soviet-era industrial sites, have lost their importance as the geopolitical situation has changed.

“No wonder some of them are open to diverse initiatives and offer a refuge to musicians, DJs, artists, and other non-commercial fringe,” he said. “An absence of commercial solutions often paves the way to cultural ones.”

In today’s Ukraine, alas, all military installations and public shelters are being used by troops and civilians. But there's a hope that one day free Nightingale of Mariupol will be able to sing without a bomb accompaniment and all the spaces will be filled with culture.