Rūta STANEVIČIŪTĖ | Microtonal Music: From the Baltic to the Adriatic and beyond the Atlantic

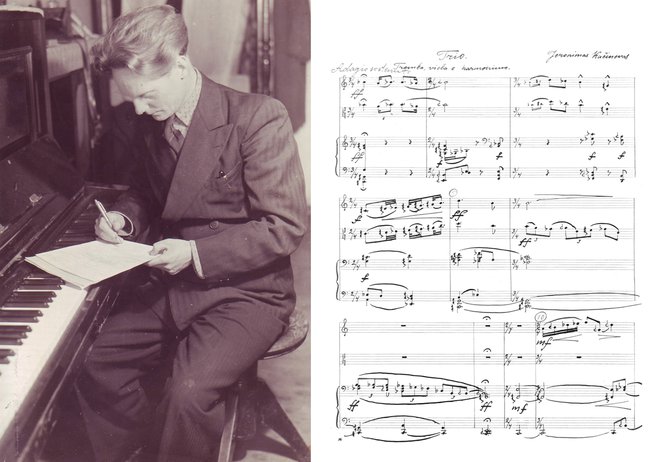

After World War II, microtonal music was regarded as an avant-garde utopia that was not destined to be reborn and establish itself. This was also the opinion of the pioneer of Lithuanian microtonal music Jeronimas Kačinskas (1907–2005), who after the war found himself as an émigré in the USA where he did not continue his microtonal experiments. Kačinskas not only did not find a favourable environment for this, even though he had settled in Boston (which was eventually to become one of the centres of microtonality in the USA), but also believed that the interwar projects and in particular the ambitions to offer a universal language of contemporary music, nurtured by his teacher Alois Hába( 1893–1973), were overshadowed by new trends and technologies. In the 1930s, Hába’s aspirations to surpass Arnold Schönberg’s school were fuelled by mass emigration from Germany and Austria. However, at the beginning of the Cold War it was precisely dodecaphony and serialism that became the new lingua franca. While to Kačinskas it seemed that the microtonal movement propagated by Hába did not fully realise its possibilities not because of the spread of the ideas of the New Vienna School but because of being overshadowed by musique concrète and other ways of manipulating the musical and non-musical sound. It is a paradox that the Slovenian composer Vito Žuraj (b. 1978), a representative of another periphery of the European musical avantgarde connected to the Alois Hába School, stated in 2015 that ‘today many contemporary composers also write only microtonal works.’ ‘He, among some other composers today, accepted microtonality as a common compositional vehicle.’[1] How could such a change have taken place? And if the practice of microtonal music is as widespread today as the Slovenian composer claims, does anything connect it to the historical microtonal avant-garde movement? It was also in 2015 that these questions brought several musicologists together to discuss the spread of the Alois Hába School and related phenomena in Central and East Europe.[2] A whole group of Lithuanian, Russian, Czech, Slovenian, Croatian, Serbian and Austrian composers, performers and musicologists soon joined this initiative – and that is how the collective monograph Microtonal Music in Central and Eastern Europe: Historical Outlines and Current Practices came into existence.[3] One of the most important aims of the publication was the consolidation of the perception of microtonal practices from the Baltic to the Adriatic. Even though there is no one standard description that can appropriately be used to give a name to this region, it most often remains on the other side of the grand narratives of the European avant-garde movement or the current global dissemination of music.

It is perhaps only natural that the first attempt to combine the previously disconnected ideas and practices of microtonal music opened up a number of hitherto unexplored phenomena, while at the same time raising a whole host of new questions. For example, microtonality in Lithuania for a long time was associated only with the composers Jeronimas Kačinskas and Rytis Mažulis (b. 1961). On going deeper, it becomes clear that episodic attempts to use microtones are to be found in the work of Vytautas Barkauskas (1931–2020) and Jurgis Juozapaitis (b. 1942) in the 1970s, and then, after 1990, microtonality became widespread in the work of composers from different generations – from Rytis Mažulis, Onutė Narbutaitė (b. 1956), Šarūnas Nakas (b. 1962), Vytautas Germanavičius (b. 1969) to Marius Baranauskas (b. 1978), Egidija Medekšaitė (b. 1979), Justė Janulytė (b. 1982), Justina Repečkaitė (b. 1989), Simas Sapiega (b. 1990), and others.[4] All the same, these individual expressions cannot be called a continuous trend in Lithuanian music.

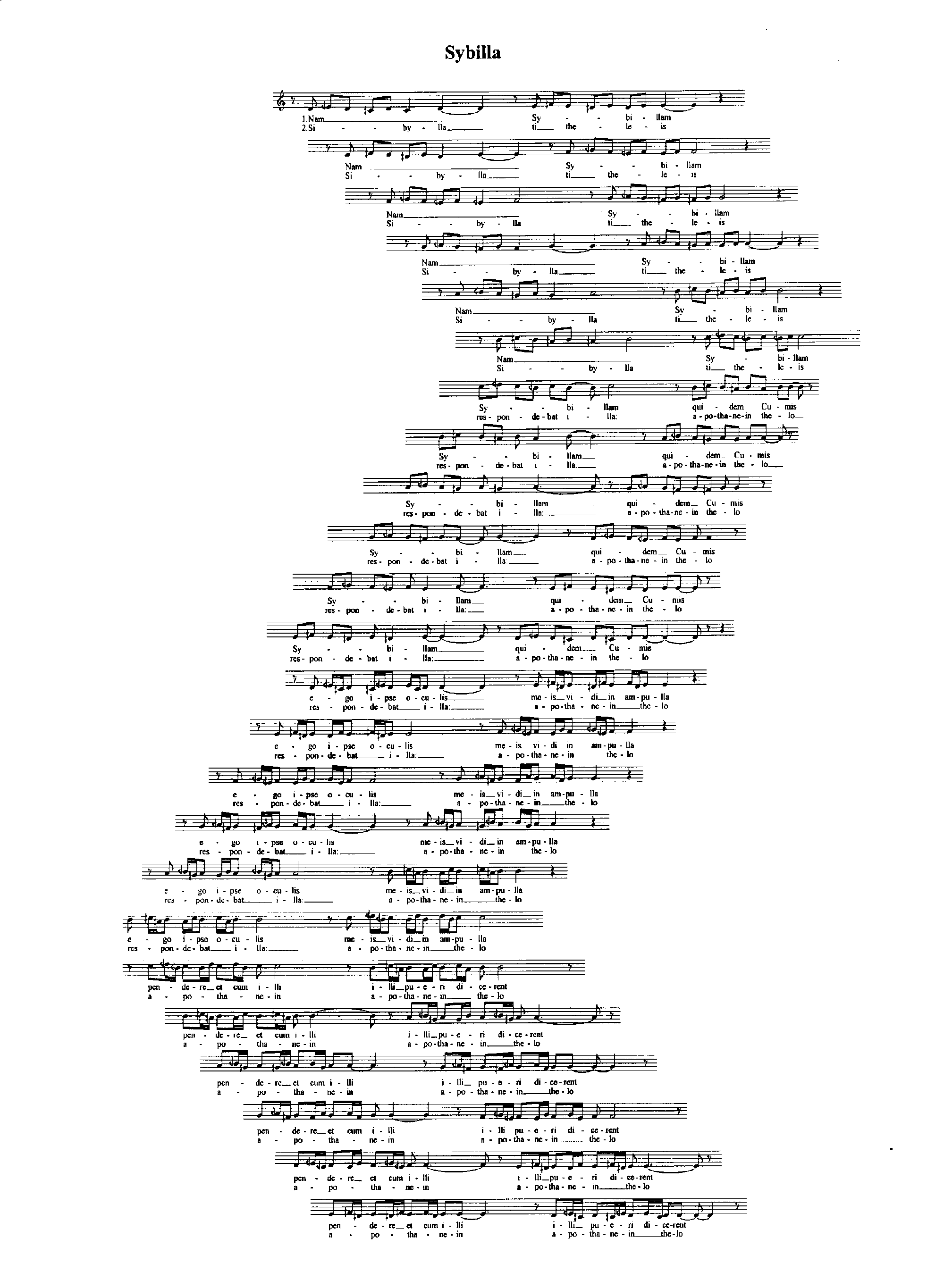

Jeronimas Kačinskas’ early quarter-tone compositions, written in the 1930s, were not performed until 2017, when compositions considered lost were found at the Czech Museum of Music and the Prague Conservatoire. In other words, Kačinskas acted only as a symbol of the avant-garde in the later spread of microtonality in Lithuanian music and as a reminder of a lost tradition. It can be surmised that episodes of microtonal music in the work of Barkauskas and Juozapaitis appeared under the influence of the innovations in second wave avant-garde composition. On the other hand, examples of Lithuanian microtonal music over the past three decades have quite different origins and sources of inspiration not limited to just the European music of various epochs – echoes of Arabic and Indian traditional music are especially common here.Similarly, the splintered tradition of microtonality is characteristic of other countries from the Adriatic to the Baltic. Undoubtedly this was due to the lack of access to the microtonal music of the first half of the 20th century – it was not only in Lithuania that many works were lost or gathering dust in archives, often still waiting to be performed for the first time. Even with the help of historical microtonal music scores, a major obstacle was the lack of authentic historical instruments specially made to perform this music. For this reason, a musical image of the most influential movement in the region mentioned above – that of the Alois Hába school, based on specific performances, has not been recreated. More often it has been reconstructed based on the responses of contemporaries or the comments of that school’s representatives themselves and in performance it presents one with surprises. Surprises like that – or, to be more precise, unexpected impressions – were provoked by the premiere of Jeronimas Kačinskas’ Trio for trumpet, viola, and harmonium in the quarter-tone system (1933) in Vilnius in 2017. The composer had planned for his composition to be performed on quarter-tone instruments which he had acquired together with his fellow musicians. In the 1930s, he had formed a quarter-tone ensemble and planned international tours but failed to put that into effect.

In 2017 some enthusiastic musicians – the pianists Motiejus Bazaras and Mykolas Bazaras, the trumpet player Laurynas Lapė and the violinist Tadas Dešukas – performed a composition without special historical instruments for the first time. This performance without any pretence to an accurate historical reconstruction was not only informative and effective but also confirmed that Kačinskas was a talented disciple of Hába and at the same time a unique talent. Associations with the Second Viennese School were also to be felt in the sound aesthetics and articulation of the whole in Kačinskas’ Trio. One should remember that he became acquainted with Schönberg’s music while still in Klaipėda, that is, before he went off to study at the Prague Conservatoire in 1929.The historic impulse of the pioneers of microtonal music as an inspiration for today’s movement is not limited to just Lithuania. Besides the oft-mentioned Alois Hába, one should also remember Georgy Rimsky-Korsakov, Arthur Lourié, and Arseny Avraamov in Russia, Julián Carrillo in Mexico, Ivan Wyschnegradsky in Paris, Jörg Mager, Richard Stein and Willi Möllendorf in Germany, Charles Ives and Harry Partch in USA, Adriaan Daniël Fokker in the Netherlands, Slavko Osterc in Slovenia, Franz Richter Herf and Rolf Maedel in Austria, as well as many others.

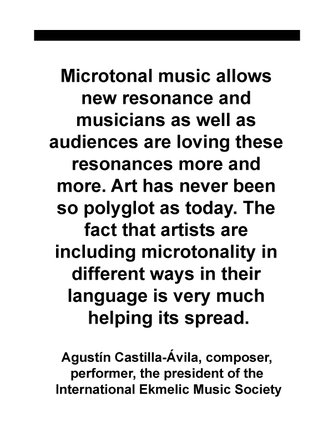

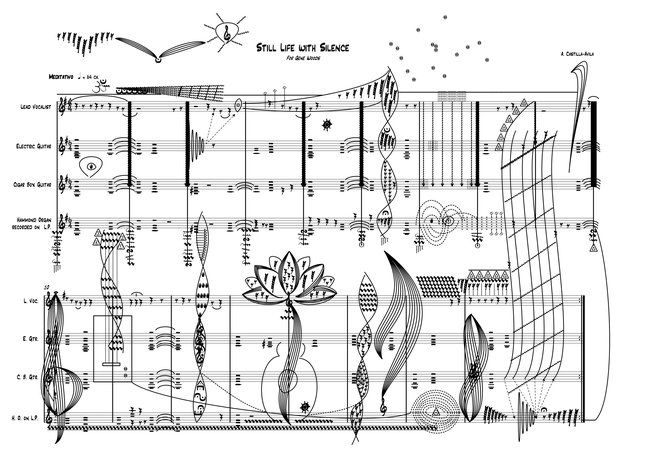

As today’s global ever-expanding microtonal music movement shows, historical memory has an impact. In addition to the long-standing American Microtone Music Festival in New York from the 1980s on or MicroFest set up in Southern California in the late 1990s, the somewhat newer International Ekmelic Music Society’s symposiums in Salzburg, Microfest Amsterdam, Helsinki Microfest and miCROfest Zagreb, two new events – namely, Microfest Prague and Microfest Vilnius – should have joined the network of festivals in 2020. Because of the pandemic the newly initiated festivals in Prague and Vilnius have been postponed to 2021. Nevertheless, the initiative itself shows the vitality of the historical origins.Festivals and other events of the growing microtonal music network provide the intriguing possibility of hearing the legendary compositions of the historical avant-garde and the post avant-garde and comparing expressions of microtonal music from different periods. The differences are obvious. If the microtonal music of the beginning and middle of the 20th century was a utopian space, then microtonality after the post-modern breakthrough was one of the mediums or techniques in coexistence with a host of other musical materials or systems. Another characteristic tendency is the poly-genre nature of contemporary microtonality, very often mixing the genres of art music, jazz, and world music.

The multi-faceted nature of contemporary microtonality lies partly in the fact that from the very beginning it never yielded to strict descriptions: ‘a cultural-historical concept [which] represents a striking collection of historical and contemporary musical movements.’[5] It has at the same time the inexhaustible ability to treat musical material with the purpose of overcoming the boundaries of the equal temperament of twelve notes per octave. Besides that, in the microtonal movement of the 21st century the performer is a no less important figure than the composer – it is no coincidence that today this music is very often created by composer-performers. It is also a fact that interpretations of classic microtonality from the beginning and middle of the 20th century merge into the historical performance movement. This was especially vividly illustrated by the concerts and projects dedicated to Harry Partch at festivals in 2019 for which the composer’s own authentic instruments had been carefully chosen (the Charles Corey lecture-recital at the Mikrotöne: Small is beautiful Symposium, International Ekmelic Music Society, Salzburg, 2019) or the specially recreated instruments to perform his music (the Scordatura Ensemble programme Harry Partch – Lecture 1942, MicroFest Amsterdam, 2019). A no less impressive expression is the attempt of contemporary composers to make the futuristic instruments of the past like Fokker’s organ or Carrillo’s piano ‘talk’.The spread of opportunities to perform music live and the innovations in musical instrumentation are two of the additional factors in the revival of this phenomenon of microtonal music long held to be a niche activity. All the same, the most important driving force in today’s microtonal music movement is the radical change in global music practices – and at the same time the constant renewal and expansion in the imagination and experience of both creators and listeners.

Translated from the Lithuanian by Romas Kinka

[1] Leon Stefanija. Microtonality in Slovenia: The Concept and its Scope. In: Rūta Stanevičiūtė, Leon Stefanija (eds.). Microtonal Music in Central and Eastern Europe: Historical Outlines and Current Practices. Ljubljana: Ljubljana University Press, 2020, p. 45.

[2] Session ‘Microtonality in Central and Eastern Europe: Alois Hába’s school and beyond’ at the 45th International Baltic Musicological Conference Composition Schools in the 20th Century: The Institution and the Context, Vilnius, 2015.

[3] Rūta Stanevičiūtė, Leon Stefanija (eds.). Microtonal Music in Central and Eastern Europe: Historical Outlines and Current Practices. Ljubljana: Ljubljana University Press, 2020. Free access online publication: https://doi.org/10.4312/9789610603122.

[4] For more see: Rima Povilionienė. From Tone Inflection to Microdimensional Glissando: Observations on Microtonal Manner in Contemporary Lithuanian Music. In: Ibid., pp. 67–113.

[5] Cf. http://www.huygens-fokker.org/microtonaliteit.html