Rūta SKUDIENĖ | (Un)forgotten Melodiya. The 60th Anniversary of the Vilnius Recording Studio

Numbers and dates. What significance do numbers have in the life of a person or a country? Lithuania will be marking the centenary of its independence by naming, as is only right, the most important events and facts of a modern Lithuania once again in its rightful place on the map of Europe.

At the beginning of the 20th century, extremely favourable objective conditions arose for a radically new approach to things to universally take hold: technical progress, speed and distance records, openness to the world, and a developing city infrastructure. In the first decades of the 20th century recordings and the cinema changed the world to an unrecognisable degree. A new understanding of music and the arts was being formed, the entertainment industry and leisure culture were developing.

The first Lithuanian disc was recorded in 1907 in Riga still quite a long time before the declaration of Lithuanian independence in 1918. An impressive archive of the first sound recordings on shellac discs, as well as from the 1920s and 1930s, collected and preserved by collectors, has survived. The recordings were made and issued by foreign record companies in Europe and the USA.

Lithuanian radio recently marked its 90th anniversary.[1] In 1940 an Iron Curtain descended and was to cut Lithuania off from the world for half a century. That is our history. Sound recordings during the Soviet period became an ideological ‘strategic’ sphere, into which a lot was invested. Let us continue with our list – Lithuanian television this year is marking its 60th anniversary (it began broadcasting in 1957), the Vilnius Recording Studio, set up in 1958, would if still active also have had its 60th anniversary in the autumn of 2018. The studio carried out its work independently and actively until 2004, but the free market is merciless and it was impossible for it to survive without the state support. The greater part of the most important work was carried out between 1958 and 1990, with relations with the record factories in Riga and Moscow being maintained right up to the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991.The digital revolution at the end of the 20th century irreversibly wiped out (that is how it looked then) the epoch of vinyl. The production lines at record factories were dismantled without any sentiment. Sound engineers and performers were waiting for innovations in digital technology, which would later have a marked influence not just on changes to technical audio and video recordings but also on artistic, creative, qualitative, ethical and aesthetic factors.

With the collapse of the Melodiya company, the republic’s sound archives were scattered, some of the recordings were transferred to foreign record companies. Luckily, the Vilnius Recording Studio’s archive was preserved, the contents entered into a list, and is professionally kept on the original tapes in the Lithuanian Central State Archives, in the sound and video section. The National Martynas Mažvydas Library also keeps copies of released recordings.

Europeana, the largest European digital platform of sound and videos, as well as various other documents, invites member countries to share their cultural heritage, to join the new system of sharing cultural heritage, accessible to all. There is certainly plenty to share. We only need to know and value what we have.

In the post-war years, during the Soviet period in the 1940s and 1950s so-called ‘sound recording brigades’ would come to Vilnius from Moscow and record the best-known opera soloists and performers of the time. Lithuanian records were made/pressed in one of the oldest record factories in Europe, that is, at the Riga record factory, called Līgo in 1958, Melodiya in 1962, and with the setting up of the all-unions company under the same name, in one of the main record factories of this monopolistic record company.

The Vilnius Recording Studio, set up on 10 September 1958, was officially for a time a branch of the Riga record factory Līgo. Up to 1962 the workers in the studio did not have a building of their own, they shared quarters with Lithuanian Radio in Konarskio street. Lithuanian radio recordings that were technically and artistically of a higher quality were chosen for the records being made.In 1962 the Vilnius studio moved to a 19th century building in what was then called the Youth Park at Barboros Radvilaitės street no. 8 (now the Bernardine Garden in Sereikiškės Park), where one already had the House of Folk Arts and the offices of the organisers of the Song Festivals. The ground floor was reconstructed and the acoustics adapted for a recording studio. In the large 280 square metre hall 32 pyramid-shaped units, reminding one of stalactites, were hung from the ceiling and 5 sound-absorbing panels, named Bekesy panels in honour of the Hungarian creator Georg von Békésy.[2] Judged by the standards of those times, the premises and equipment of a studio of this kind were among the best to be found in the Baltic states.

In 1964 the all-union Melodiya company was set up and one of its branches became the Vilnius Recording Studio right up to the second restitution of Lithuania’s independence. There were recording studios in operation in Moscow, Leningrad, Tbilisi, Tashkent, Alma-Ata, Riga and Vilnius, and premises where equipment was kept in Kiev. Recordings also took place in premises with natural acoustics in what was then the Vilnius Picture Gallery (now the Vilnius Cathedral). At the end of the 1980s the studio equipment consisted of a multi-channel recording machine, a new audio console, and in the main hall – Petrof and Bechstein grand pianos.

All the same, the central Melodiya studio in Moscow was technically much better equipped. Judged by today’s technical standards, the opportunities were modest. Audio engineers were required to have considerable practical skills, as well as technical and musical training. The quality of musical sound and the emotional impact depended on the hard, demanding work of the audio engineer and the performers. Because of street noise from outside the studio premises, recordings took place in the evenings, often continuing into the night.

On the one hand, subordination to the former Ministry of Culture of the Soviet Union was an inhibition and obliged obeisance to the Soviet cultural system, but, on the other hand, it was a defence against the excessive zeal and dictates of local political functionaries. In leafing through the catalogues issued by the Vilnius studio right from 1959 to 1974 and later, one can only be amazed by the variety of music that was recorded, with the records carefully grouped according to genre. Besides recordings of music, there are also quite a few recordings of literature, Lithuanian folk tales for children, folk music, restored recordings, methodological teaching materials and special commissions. One should not forget that the plans regarding releases were made only with the agreement of Melodiya and the officials in charge at the Lithuanian Ministry of Culture. Priority without exception was given to Soviet ideology. Compositions with names like ‘Lenin sees’, ‘Ballad about the stoker on steam engine no. 293’, ‘Song about the Party’, and other similar ones, characteristic of that time period considered ‘valuable from an artistic and ideological point of view’, can be found only amongst early releases from the 1950s and 1960s.

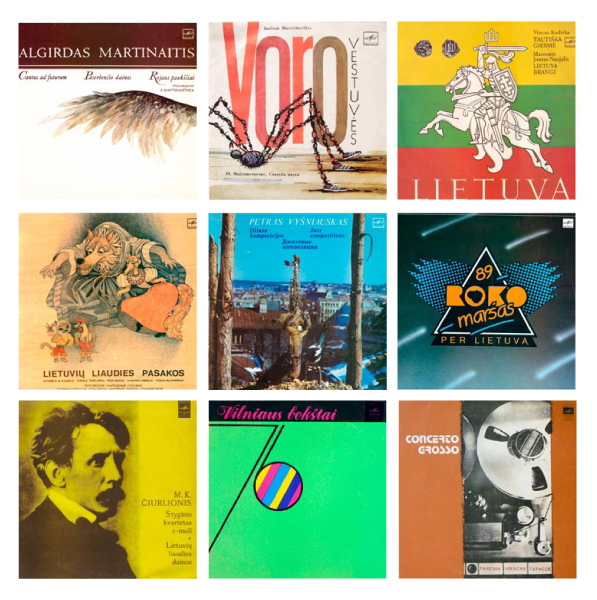

At the end of the 1960s, records were begun to be specially designed and it was decided to no longer use the standard covers. Between 1964 and 1970 thirteen sets of records were issued in special packaging, which today have become bibliographic rarities, for example, an anthology of the music of Mikalojus Konstantinas Čiurlionis, issued to mark the 90th anniversary of the composer’s birth; Voices of the Writers of Soviet Lithuania; selected recordings by the ensemble Lietuva (Lithuania); Anthology of Lithuanian Folk Songs; restored recordings of music sung by the operatic tenor Kipras Petrauskas; Juozas Gruodis’s symphonic and chamber compositions. Professional artists were invited to design record covers. Before they were produced, the artistic quality of the covers was first deliberated over by arts committees both at the local level and at Melodiya.

The studio was the only creative organisation in Lithuania for the release and distribution of Lithuanian music and word recordings, working relatively independently (at the time Lithuanian radio and television programmes were much more strictly censored). It recorded and prepared for release collections of the work of the composers already mentioned above, as well as that of Juozas Naujalis, Stasys Šimkus, Jurgis Karnavičius, Balys Dvarionas, Eduardas Balsys, Julius Juzeliūnas, Osvaldas Balakauskas, and Bronius Kutavičius; the series Soviet Lithuanian Composers; works by young composers of the 1970s and 1980s; the series ‘Lithuanian Organs’; recordings by the Lithuanian Chamber Orchestra and various string quartets; collections of Lithuanian folk music; recordings by ensembles; the plays of Justinas Marcinkevičius; the poetry of Maironis and Vytautas Mačernis; recordings of the songs festivals; work by composers of estrada[3] songs and recordings by various ensembles playing the same kind of music, and the electronic music group Argo; restored recordings of opera soloists from the 1920s and 1930s; recordings by small stage performers from the interwar period. We have recordings of the first jazz festival Jaunystė-68 (Youth-68) in Elektrėnai, the Vilniaus bokštai (The Towers of Vilnius) competitions for performers of estrada songs, and the Birštonas Jazz Festival, albums by the Vyacheslav Ganelin / Vladimir Chekasin / Vladimir Tarasov Trio, the Petras Vyšniauskas Quartet, Gintautas Abarius, Kęstutis Lušas, and others. Ignored by Lithuanian radio and television during the Soviet period, the ideologically unwelcome bard Vytautas Kernagis, thanks to the clever strategy of the editor Zina Nutautaitė, was successfully recorded at the Vilnius Recording Studio. In 1974 Ganelin’s music for Arūnas Žebriūnas’s film The Devil’s Bride was recorded and released as a double album. During the period of revival, as it is called, before independence, records by the group Antis, the music of the Rock Marches and the rock music festival Lituanika-87 were released. Mentioned here are only some of the recordings which without any reservation should be regarded as part of Lithuania’s cultural heritage.Music composed for feature films produced by the Lithuanian Film Studio and for plays put on by Lithuanian drama theatres were also recorded at the Vilnius Recording Studio. The record producers working in the studio were self-taught. At that time there was simply no school or courses for audio engineers. Vytautas Einoris, Vytautas Bičiūnas (the only one to go abroad to study audio engineering, in his case to study under the audio engineer Antanas Karužas at the Warsaw Higher State School of Music, and who taught a course on the acoustics of music at the Lithuanian Academy of Music and Theatre), Vilius Kondrotas, the brothers Eugenijus Motiejūnas and Rimantas Motiejūnas were all self-taught. They all worked selflessly, not counting the number of days or hours they worked, and deserve our respect.

During the last years of the studio’s existence, history paradoxically repeated itself: ‘digital sound recording brigades’ would come from Moscow, with the Melodiya audio engineer Eduard Shakhnazarian, an editor and a mobile digital studio, the so-called ‘tonwagen’. The privilege of being recorded digitally was granted to the highly regarded Lithuanian Chamber Orchestra, directed by Saulius Sondeckis. The recordings took place in the Cathedral (then the Vilnius Picture Gallery), not yet returned to the Catholic Church. According to Shakhnazarian that was the best acoustic environment for recordings… Later, St John’s Church was used to digitally record fragments from Modest Mussorgsky’s opera Boris Godunov, performed by the Lithuanian National Symphony Orchestra with Vaclovas Daunoras as the soloist, as well as Čiurlionis’s symphonic poems performed by the Lithuanian State Symphony Orchestra (Melodiya’s sound engineer Yuriy Vinnik was specially invited by the studio for the recordings). The number of Lithuanian records under the Melodiya brand was not large. The print runs were set by the organisations dealing in the recordings. Pressings of classical music ran to only 500–1000. The largest print runs were of light Lithuanian music performed by ensembles like Kopų balsai (Voices of the Dunes) and Nerija, Maironis’s lyrics,[4] Vytautas Kernagis, etc. Lithuanian light entertainment music in the Lithuanian language could not compete on the general Soviet market, nor was there any opportunity for Lithuanian recordings to reach markets on the other side of the Iron Curtain, but they were popular and well-regarded by Lithuanian exiles living on the other side of the Atlantic. Going the full circle – from Vilnius to Moscow, passing (or not) the technical control test, listened to in the arts council, prepared for printing, manufacture, going to the Riga record factory, the records would come back to shops in Lithuania. This ‘musical journey’ would take two to three years. The unsold records, returned by the sellers to the factory, would be melted down and new records made from the old ones… Perhaps for that reason the quality of some Soviet records was poor and made a hissing noise. The business of selling records only improved during the perestroika years, shops that specialised in certain kinds of music made their appearance in Vilnius and in other towns in Lithuania. Records made for export were of a better quality. Melodiya did not inform its employees as to whose music would find its way to the international record market. There is information that those were the recordings made by the Lithuanian Chamber Orchestra, the ensemble Lietuva, the Ganelin Tarasov Chekasin Trio, and the tenor Virgilijus Noreika.After 1991, quite a few of the studio’s recordings were transferred as CDs to Muzikos bomba, some to Music Information and Publishing Centre Lithuania, Zona and others. Deserving of special mention are the publications in 1992 of the Japanese company King Records, taken from the archives of the Vilnius Recording Studio. CDs appeared after the exhibition of Čiurlionis’s paintings in Tokyo in 1992 and were distributed all over the world. In 1991 the above-mentioned recording of Čiurlionis’s symphonic poems was digitally issued, as well as a double album of his compositions for piano (originally recorded in 1975) and folk songs for choir.

The epoch of vinyl and analogue recordings is returning. Sound quality experts and collectors only place value on those vinyl disks which have been correctly transferred from the original studio tapes. The sound of even old shellac disks or mono recordings from a later period should not be artificially corrected or ‘improved’ – we would be losing authenticity, the sound of a by-gone era.

The former Vilnius Recording Studio’s premises now belong to the National Folk Culture Centre. There are large windows in the north-facing wall of the hall in the former recording studio and recordings are still being made here. The ceiling pyramids regulating the acoustics have survived. The centre is actively up-dating its equipment, however… the illuminated sign saying ‘Silence! Recording in Progress’ would look old-fashioned.

Translated from the Lithuanian by Romas Kinka

[1] Société française radio-électrique, a French company, built the Kaunas radio station in 1925 and the following year Kauno radiofonas (Radio Kaunas) began its broadcasts.

[2] Darius Pocevičius, ‘Ką mena stalaktitų lubos Vilniaus plokštelių studijoje’ [The Importance of the Stalactite Ceiling in the Vilnius Recording Studio]. Literatūra ir menas, 05 05 2017, No. 3614.

[3] Translator’s note. Estrada is a term encompassing popular ‘small stage’ music genres like gypsy romances, tangos, foxtrots, small and big band jazz, etc. It comes from the French word estrade (‘platform’). David MacFadyen in his book Estrada?! Grand Narratives and the Philosophy of the Russian Popular Songs since Perestroika (London, 2002) writes that the “inclusion of soul and disco hinted at estrada’s anachronistic merging of traditions”.

[4] The print runs of Maironis’s lyrical poetry, regularly reissued from 1971 up to the end of the 1980s, reached a figure of as much as 100,000.