Kutavičius Gone Astray

- June 25, 2015

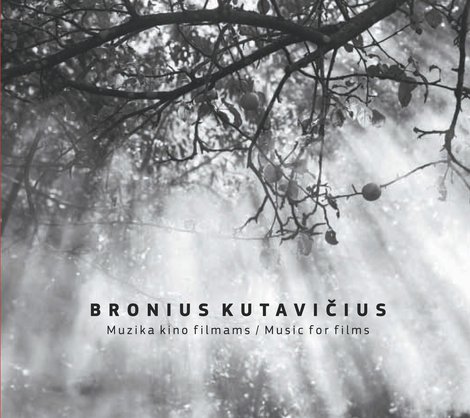

The CD Bronius Kutavičius. Film Music released by the Music Information Centre Lithuania appeared on the scene like some kind of agent provocateur, disturbing the accents of Lithuanian music legitimised a long time ago, the myths created by both composers and their adoring public, as well as the contextual shores still hidden in the mist.

First and foremost, what grabs one's attention is the variety, the inventiveness and the mesmerising quality of the music which do not square with the myth that has taken hold that film and theatre music during the Soviet period was for composers just a job to earn some money and a 'creative laboratory' in which they would try out certain ideas and technical tricks to be used later in their 'real' work. More than one composer has asserted this. I cannot say for a fact if Kutavičius has ever said that. But even if he never has, that is most probably because no one ever asked him. And he was never asked because that is NOT WHAT Kutavičius should be asked. The supposedly casual approach of composers to film music reminds one of the no less fashionable cliché held by actors at the time that theatre is, supposedly, where real creativity lies and cinema is just an insignificant deviation from the right path. However, in watching the films of that period, what often amazes one is the talented acting of the actors, which in no way could one call a deviation. And if, moreover, we were to remember that Soviet films were shown from Vilnius to Vladivostok, from Sochi to Arkhangelsk, there is no doubt that an actor who had created a distinctive role would have been recognised in the street and not just in Vilnius. Of course, that is not what is most important but almost all those actors who had worked in films later admitted that they were sorry that that they had been used too little, in other words, that they had not gone astray often enough. Even though people did not turn around to look at film music composers in the street, I have no doubt that work in the cinema gave rise to strong emotions and a wish not to disappoint a film director if he had chosen you. Besides that, millions of people would see the film and one's colleagues would pay attention to one's music. So, there is no doubt that film music composers would make the effort to be interesting, innovative, relevant and at the same time more democratic, more easy to understand than in their 'real' work in which they could not be relaxed because of the need to do something OUT OF THE ORDINARY, as if each new composition were a debut. Otherwise one could be criticised for repeating oneself... And, of course, there were no guarantees that after the first composition another would come along. And here was film seen in cities and on communal farms and even in every home with a TV. After all, a composer repeating himself in his film work became an asset, a sign, that he was predictable and a suitable partner to achieve the intended result. So why were composers so casual in the evaluation of their work for the cinema? Especially since cinema for the Soviet government was the most adored of the arts from the times of Lenin's well-known maxim: 'Of all the arts the most important for us is cinema.' Most probably because in the undefined pyramid (or perhaps one defined in some Central Committee decree?) of Soviet culture cinema was relegated more to the sphere of acceptable leisure (i.e. entertainment), while concert music served high art. In line with that, a hierarchy of value was introduced. The work of composers for the cinema used to be written about in brief , without any pretence to a wider analysis at the end of monographs or portrait sketches, usually with reference to a 'creative laboratory,' as if in this way to justify 'deviation.' Thus, film music received validation as a lower form of creative work, and those that were strongly involved in it were disparagingly referred to as mere film music composers. Of course, there were dozens of composers who really did dedicate the style they had created to the mass production of Soviet films about war, the life of workers and collective farm labourers, as well as the battle for the ideals of socialist realism. However, could we call Alfred Schnittke a mere film music composer, someone who had written the emotional and colourful music for the first Soviet disaster film Air Crew (1979; directed by Alexander Mitta), or Eduard Artemyev, who introduced a new meaning in music for the cinema in Andrei Tarkovsky's Solaris (1972), The Mirror (1975) and especially in Stalker (1975)? By the way, Nikita Mikhalkov, that famous Russian discoverer of talent, markedly later in the new Russia brought Artemyev on board as a certain guarantee of success for his Hollywood-style epic The Barber of Siberia (1998). In the West, film music began to develop quickly, almost as soon as the silent film era had come to a close. Many composers turned to the film industry not just because of the new opportunities it presented but also because of the substantial financial rewards for copyright. Within a short time, the great Hollywood directors and those on the old continent made the names of their favourite composers famous. And so the names of Nino Rota, John Williams, Vangelis, Ennio Morricone, Richard Addinsell, Richard Rodney Bennett, Michael Nyman and others entered the history of music and pop culture. In the Soviet Union, on the other hand, film composers were almost anonymous, even though their names flashed up on the screen amongst the small lines of the titles. Composers did not receive a percentage of the take from the ticket sales. In other words, regardless of whether the film was successful or not, composers received a one-off fee for the work they had done. Therefore, film music because of its reduced socio-cultural significance did not have the opportunity to come up even to the level of popular music and found itself in roughly the same place in the Soviet hierarchy as circus music. An exception perhaps was Andrey Petrov who became famous through his songs in the films directed by Eldar Ryazanov. Well, there was also Isaak Dunayevsky.It would be hard to imagine that during the Soviet period Melodiya, the only vinyl record company in the Soviet Union, would have released film music (unless that music was as Tchaikovskian as that of Eugen Doga's waltz from the film My Affectionate and Tender Beast (also known as A Hunting Accident; 1978, directed by Emil Loteanu) or that the music would be reworked and arranged as suites, like that, for example, of the composers Nino Rota or Ennio Morricone. In this respect, an exception was Eduardas Balsys, who all his life had tried to make film music legitimate as work that was not a deviation from the right path and was worthy of being heard not just in a film, and so he would later rework the melodies heard in the cinema into pop songs, pieces which were to be made popular through radio. Otherwise, Soviet film music was laid to rest together with the film reels gathering dust on the shelves in archives. However, sometimes a gust of fresh wind would blow through the archives. One of those gusts blew into the drawer with the Lithuanian film reels with the music of Bronius Kutavičius in it.

Lithuanian cinema became famous because of its melancholic and poetic nature. That was especially characteristic of the films made in the '70s and '80s, a period during which Kutavičius quite often worked in the Lithuanian Film Studio. The official Soviet doctrine preached 'mature socialism', while in the arts an increasingly strong individual voice was slowly chipping away at the foundations of the system, awakening in society a longing for sincerity, a sense of community, national traditions, spirituality, religiousness and freedom. We can recognise this aura both in the films directed by Lithuanian directors and in the cult works of the time by Kutavičius, and we can expect to find the same in his film music. But here we come face to face with some surprises, forcing us, whether we like it or not, to rethink the world view of Kutavičius's work. On the one hand, some of the musical fragments that found their way on to the CD are stylistically recognisable, characteristic of Kutavičius, but the majority of them force one to shrug one's shoulders. Really?! In his 'real' music Kutavičius is very consistent, recognisable from his specific archaic minimalism, while half of the film music pieces on the CD are so stylistically diverse that one would never even suspect that they were the work of the composer of 'The Last Pagan Rites", a seminal work of Lithuanian musical culture. One may also entertain doubts as to the question of the 'creative laboratory.' Which came first - the chicken or the egg? If we remember the composers asserting that in working for the cinema they were searching for new things which they would later use in concert music, then this CD as a document tells us something different. For example, in listening to how the actors Algimantas Masiulis and Valentinas Masalskis (Father and Son in Gytis Lukšas's film Summer Ends in Autumn, 1981) sing the romantic song 'The Cornflower,' out of the intonations of which are put together nostalgic variations, and from memory rise up the idea and dramaturgy behind Dzukian Variations, composed in 1974. I heard the same model of variation also in the small fragment from Henrikas Šablevičius's 1979 film Our Small Sins. Therefore, it is not clear for whom this was more a 'creative laboratory.' In the final analysis, that no longer has any meaning. What is important is that this CD supplements in an interesting way the totality of Kutavičius's work, showing him to be a flexible, sensitive composer, with a feel for every rhythm employed in a film, the narrative tension, emotional background, to which he skilfully adapts, finding the appropriate colours and forms. This flexibility and inventiveness of the composer is the greatest discovery and value of this CD. After all, the work that is performed in concert halls is stylistically unmistakeable and the aura of its sound such an integral part of the composer's image that when one hears fragments from Raimondas Vabalas's 1980 film The Match from 9 till 9 one can shout out in surprise! The lightly 'arranged' J. S. Bach style 'preludes' and 'fugues' in a swing style remind one of The Swingle Singers, the cult British vocal group of the time. The composer chose this style to depict the everyday existence of a modern city and to accentuate an urban ethos.On the CD there are also excerpts from two of Kutavičius's works that have 'not gone astray.' Those are fragments from his opera Thrush - the Green Bird, that found their way there because Jonas Vaitkus in 1990 made a film-opera based on a work that had been staged earlier. This music brings us back to the style and themes used by Kutavičius that we are familiar with. The second work on the CD is the music composed in 2009 for Carl Theodor Dreyer's silent film The Passion of Joan of Arc (1928). This music unites, as it were, an otherwise stylistically diverse disc. On the one hand, the music has its own form and developmental logic as an independent work; on the other hand, its dramaturgy, the alternation of contrasting episodes is dictated by the narrative and scenes in the film, and so one can say that in its spirit it is more a film music composition than a concert one.

This collection of Kutavičius's film music is a discovery for several generations. And I would dare to guess once more that this work is more important to the composer himself than it might seem. Therefore, it would be right to include his film music in the lists of his works as an important, original and distinctive part of his oeuvre. Generally speaking, one very much wishes for other gusts of fresh air to also blow through the shelves of other archives on which film reels with the music of other Lithuanian composers sit silent.

Jūratė Katinaitė

Translated by Romas Kinka