Lithuanian Music Link magazine has restarted publication

- Jan. 19, 2016

Issue No 18 of Lithuanian Music Link came out on the eve of the New Year. Publication was resumed in 2015 after a break of five years. From 2000 to 2010 MICL published Lithuanian Music Link in a newspaper format. It was and remains the only periodical in English on the musical culture of Lithuania with its main focus on contemporary Lithuanian compositional music. In restarting publication of Lithuanian Music Link, a new format – that of a magazine – has been chosen and with publication now on an annual rather than biannual basis.

The new issue has four sections: History & Context, Styles & Scenes, Composer in Focus, and Performer in Focus. The first section covers events in Lithuania’s musical history, events that have taken place inside, as it were, the political centrifuge: the singing revolution and the rock marches; the collective happenings, performances, actions initiated by Lithuania’s music community during the period of struggle for independence; and the ballet Vaivos juosta (Vaiva’s Woven Belt) composed by the modernist Vladas Jankubėnas during World War II. The second section explores the territory of Lithuania’s musical underground, popular culture and contemporary opera. The composers Anatolijus Šenderovas, Egidija Medekšaitė and Rita Mačiliūnaitė are presented in the third section, while in the last section the focus is on the accordionist Raimondas Sviackevičius and the contemporary folk and world music performer Indrė Jurgelevičiūtė.

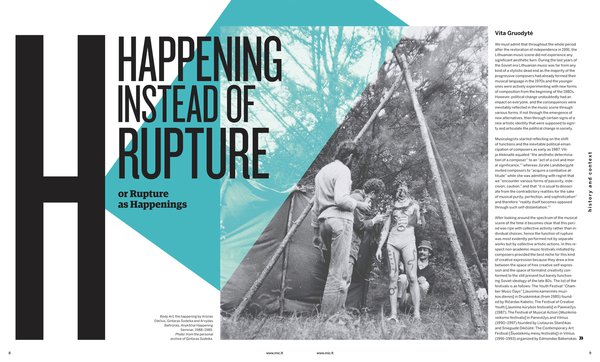

No 18 of Lithuanian Music Link is comprised of eleven texts. In the first of them the musicologist and semiotician Dario Martinelli, who lives in Lithuania, examines the musical aspects of the independence movement from 1987 to 1991 in his article ‘The Singing Revolution. One of the (Unfortunately) Best-Kept Secrets of Lithuania’. He identifies three ways in which the ideas of independence and nationalism were conveyed: 1) new music with a clear political subtext; 2) national music intrinsically in opposition to the Soviet, i.e. ‘Russian’, repertoire; 3) prohibited music, e.g. rock, despised in the Soviet Union, which embodied disobedience to the system.The Lithuanian musicologist Vita Gruodytė, who lives in France, considers the changes in new music in Lithuania over roughly the same period of 1985-1993 in her article ‘Happenings Instead of Rupture, or Rupture as Happenings’. The author writes: ‘Reactive happenings (reactive, that is, in their implementation), performances and actions became harbingers of Independence precisely because of their spontaneous reaction to the changes of that time. Leaving the institutional environment of Vilnius, where creative initiatives, limited by state censorship, progressed slowly, for the informal territories of Druskininkai, Panevėžys, Anykščiai, and Kaunas, where the artistic and non-artistic environment was not determined a priori, it became possible to create other – symbolic – places for the dissemination of art, places that encouraged the implementation of new ideas and a new approach to the function of art.’

Episodes from the history of modern music in Lithuania are highlighted in ‘National Arts in the Times of Totalitarianism: Vaiva’s Woven Belt, the Ballet by Vladas Jakubėnas’, a conversation between the musicologist Rūta Stanevičiūtė and the composer Marius Baranauskas. The work of Vladas Jakubėnas (1904–1976), one of the best-known of the interwar modernists and most influential music critics of the time, is not well known. He left Lithuania in 1944 because of the approaching Red Army and, after spending several years in displaced persons’ camps in Germany, settled in 1949 in the United States where he spent his final years. Because of the ensuing chaos a good number of his compositions were lost. Particularly dramatic was the fate of Jakubėnas’s ballet Vaiva’s Woven Belt: the score vanished together with the conductor Leiba Hofmekler who had been working on it. Hofmekler was held in a Jewish ghetto during the Nazi occupation of Lithuania and is believed to have been killed in 1941. In 1943 Jakubėnas was able to reconstruct the piano score from memory but it was only in 2014 that the ballet was staged for the first time thanks to the efforts of the Vladas Jakubėnas Society who had started to work on the project in 1993. The creative orchestration is by the composer Marius Baranauskas.

‘The days of Soviet Estrada and Eurotrash pop are over – today’s Lithuanian popular music like never before is fresh, diverse and open to the world,’ writes Karolis Vyšniauskas in his article ‘An Optimist’s Guide to Lithuanian Popular Music’. In the author’s opinion Lithuanian popular music has basically only begun to change now – 25 years after the Declaration of Independence and more than a decade after Lithuania’s entry into the European Union. However, the scene is still not progressing in one direction: ‘One day, ten thousand young people can be seen singing along with the British teen idol Ed Sheeran in the same concert hall in Vilnius, and then two weeks later Russian music stars fronted by Phillip Kirkorov are performing in the same arena.’The creative niches of the Lithuanian underground music scene, the environment in which it lives, its communities and those active in it are discussed by Jurijus Dobriakovas in his article ‘An Attempt at Mapping the Lithuanian Underground Music Scene’. In delineating the trends in experimental electronic music, noise, archaic industrialism, metal, punk, dark synthetics or dark ambient, the author emphasizes the fact that ‘the alternative, non-commercial, DIY scene constantly mutates, migrates, changes its internal structure and escapes conclusive definitions. Yet one thing is certain: it exists somewhere in some form at any given moment.’

The musicologist Veronika Janatjeva and the theatrologist Vlada Kalpokaitė in their discussion ‘New Opera Action at the Crossroads’ tackle head on various aspects of ‘New Opera Action’ and generally of the processes taking place in contemporary music theatre: cultural management, the artist’s ego, a festival’s identity, the isolated arts communities, norms of behaviour, performative and postdramatic creative work, the hybrid types of scenic genres, the platform of collective creative work and dictatorial directors. In Vlada Kalpokaitė’s opinion ‘Outstanding productions do not happen in Lithuania without the firm hand and strong will of a director. If a director’s personality has no elements of despotism and if he is inclined to give in to other influences, to think too much about creating a positive psychological climate within the company and about how to stick to the best principles of work ethics, not to shock anyone, never to raise his or her voice and so on, a production will be considerably poorer, its ideological dimension disappear, and the work become lifeless, uninteresting and without vitality. In the final analysis, all of the participants in the process will suffer, no matter how well they felt at the rehearsals.’

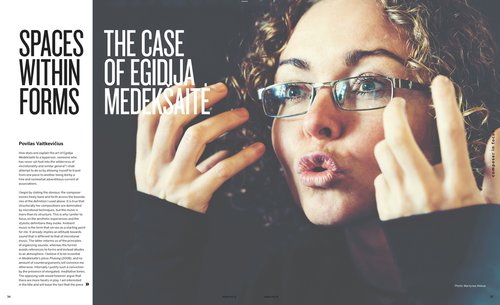

In the section Composer in Focus the portraits of three Lithuanian composers are, as it were, put on show. In Beata Baublinskienė’s interview ‘Life Comes with Change’ the focus is on Anatolijus Šenderovas, who was active in celebrating his 70th birthday in 2015. In the conversation Šenderovas reveals his views on the importance of music, the conditions for maintaining creativity, and on having an active involvement with the performers of his music.Povilas Vaitkevičius in his article ‘Spaces within Forms: The Case of Egidija Medekšaitė’ writes about the music of one of the most active composers in Lithuania. ‘How does one describe the work of Egidija Medekšaitė to someone who has not set foot in the jungle territory of microtonality and similar things?’ asks the author. He continues to go on to write: ‘Even though it is the microtonal composition method that is dominant in the constructions of her work, music after all is not just construction. […] The main role here falls to the term ambient music which in itself denotes a somewhat different approach to sound than microtonality.’

Lina Posėčnaitė writes about the work of Rita Mačiliūnaitė, another composer of the younger generation, considering her music in the context of ‘Lithuanianness’. In her article ‘Some Thoughts about Time, Place, Quality and National Identity: The Music of Rita Mačiliūnaitė in Context’, she asserts that: ‘No matter how important / universal / clearly individualistic is the musical foundation, no matter from what German / French / British cultural / religious or whatever other traditions it comes from, in the music of even the most dissimilar Lithuanian composers (and not only those) born in the 1980s, a Lithuanianness can be heard which is, in spite of everything, indelible and not possible of being mistaken for anything else.’

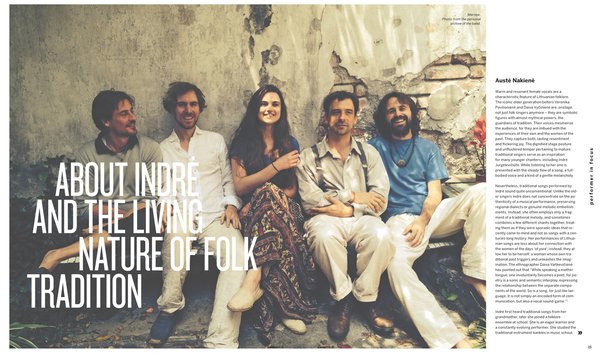

The magazine also has the accordionist Raimondas Sviackevičius in conversation with Andrius Maslekovas and Lina Navickaitė-Martinelli. An active promoter of new music and an inspiration for those in the field, Sviackevičius is constantly working to meet the challenge of preconceived notions and in a targeted way to form the image of the accordion as an instrument of and for contemporary compositional music, and in his programmes to break down the barriers imposed by the typical musical genres and repertoire.Austė Nakienė in her article ‘About Indrė and the Living Nature of Folk Tradition’ presents Indrė Jurgelevičiūtė (voice, kanklės), a performer of alternative folk and world music who is involved in various international projects. Nakienė asserts that ‘The way of singing folk songs today has less to do with imitation and more with being creative’. She goes on to write that Indrė Jurgelevičiūtė is a true ‘herbalist’, mixing elements of different styles – jazz, contemporary academic music, and archaic or bardic music.

The printed version of Lithuanian Music Link is in English. All of the content is available in English and Lithuanian on the web page of Music Information Centre Lithuania at www.mic.lt.

Translated from the Lithuanian by Romas Kinka

Information from MICL