Linas PAULAUSKIS | Many Musics

I shall begin with some introductory remarks then continue with an exposition of the subject matter under discussion. I don’t yet know if I’ll come to the final conclusions or not.

1. Why the plural? Because it seems to me that music remains the most fragmented of all art forms, like no other. Everyone knows what classical music is. The same holds true for contemporary art since we’ve all become used to seeing contemporary painting on the walls of the offices of those important companies, while the culture of contemporary art centres is also widespread. But if we ask people from different socio-cultural strata (or to make it simpler: ask those with and without an education in music) – what does ‘contemporary music’ mean to you, or even better: what is your favourite contemporary music and ask them to list some names, the answers will be as different as day and night (the same effect will be obtained if you ask what electronic music is). So, musics exist almost like separate branches of art do. But today in Lithuania there are more and more multi-talented people involved in different musics, where sometimes you can figure out – and sometimes not, no matter how hard you try – that it’s the same person doing everything.

2. A huge question is what name to give to one of the musics we’ll be discussing here: music, arising from the Western European canon and written down in scores by authors who have completed their composition studies. (They can indulge in whatever non-notational experiments they please but firstly they must have learned how to do that.) All the existing terms do not apply. Serious music? Does that mean that folk music and jazz are not serious? Contemporary classical music? A clumsy oxymoron. Art music? Art song is a more readily understood term but art music? What? Isn’t jazz art? Compositional music? But pop songs are also composed and not improvised. Academic music? But it’s far from the case that all the authors of this type of music are ‘academic’, sometimes they are emphatically ‘antiacademic’... All the same, I’m going to retain the latter term, as it is also a reference to the study of the profession of composition in music academies. But what then should we call other kinds of creative work? If it’s clear that it, e.g. rock, is there in the work of a particular author, that’s what I’m going to write – that rock is there. If we’re going to talk about more of the other different genres simultaneously, then perhaps I’ll simply call it a field of non-academic work. But even here, there’s a question – after all, jazz is also taught in the Lithuanian Academy of Music and Theatre...

3. In Lithuania, it was as if there had been nothing similar to Frank Zappa, with a monument erected to him in its capital Vilnius. He switched from his studies of academic music to rock‘n’roll because there couldn’t be the energy which he so much needed vainly in the former music. (In Lithuania there were at least a few composers who switched from academic music to ‘fast food’ pop because of money – but that, as I’m sure you will understand, is not the object of this overview.) But I thought that the creative journeys of Lithuanian composers to the territories of different musics may also be interesting or bring up something unexpected.

4. We’ll be talking about those authors who have graduated in composition, who are writing that one kind and that another kind of music, who are not just writing that other kind of music but are also performing it on stage, and mostly I’ll be talking about those who are doing that today.

Where should we begin? There are some authors whose entire oeuvre can be more easily comprehended as a whole. In the case of Algirdas Klova (1958-2021) it is the leitmotif of folk music which brings together his work and stage performances. Playing the violin, being the leader of the authentic folk music group Vydraga, performing country, bluegrass, world music, working on folk-jazz projects, he carried folk music motifs and moods over into his pop songs as well as into academic compositions, and most probably precisely because of that, the flow of those pieces is so natural and, seemingly, in alignment with the living nature.

It’s not always so simple to understand the work of other authors as one picture. And it’s worthwhile here to make a detour to the past and remember several composers, today no longer present live on the stage of non-academic music, but who have left a marked imprint. We should begin with the composer, keyboardist, carillon player Giedrius Kuprevičius.

Giedrius Kuprevičius (b. 1944) is a composer of some especially popular musicals in Lithuania, as well as operas, a lot of orchestral, chamber and vocal music, at the turn of the century he played in the world music trio Žaliakalnio vilkai (The Wolves of Žaliakalnis), presented programs of solo improvizations, but what he is most remembered for is the group Argo, which he founded at the end of the 1970s and led for a decade. It was called one of the first electronic music groups in the Soviet Union (the members were Giedrius Kuprevičius – keyboards, Julius Vilnonis – keyboards, Linas Pečiūra – guitar, Arūras Kuznecovas – bass, Arūnas Mikuckis – drums). In those times there was no possibility of easily getting the instruments necessary for this kind of music and so the members of the band began constructing synthesizers themselves.

Today we would regard the music they played as progressive rock with inserts of fusion jazz, disco and ambient. Whatever the case, that music, mostly composed by Kuprevičius, the leader, was an example for young musicians of what could be done, music that was eagerly awaited and bought by listeners throughout the Soviet Union at the time. Even though officially Argo’s music was viewed with some suspicion, their debut record Diskofonija (1980) went through many print runs; it’s now thought that in total about one million copies of this record were printed. A Lithuanian platinum record heard the length and breadth of the Soviet Union.

Vaclovas Augustinas (b. 1959), the recipient of Lithuania’s highest artistic award the National Prize for Culture and Arts, leader of the Vilnius municipal choir Jauna Muzika, a composer of mainly choral music, wrote for and played keyboards in the progressive rock band Saulės laikrodis (Sun Clock), the activities of which were practically prohibited and stopped by the Soviet authorities, accusing their music of ‘nihilism’, ‘pessimism’ and ‘subjectivism’. In 1987 Augustinas joined the political punk/post-punk group Antis (later their style extended to progressive rock, vaudeville, and finally to industrial rock). Antis was the real symbol of Gorbachev’s perestroika and later of the process of reclaiming Lithuania’s freedom. And two decades later the band’s founder and ideological leader Algirdas Kaušpėdas appointed Vaclovas Augustinas as the group’s music director.

Another composer (who is now seldom playing live on stage), Linas Rimša (b. 1969) is probably the one who can turn his hand to more things than anyone else mentioned here: besides academic music, he wrote and played jazz (on keyboards and the harmonica), world music, produced pop music albums, was the first to play acid jazz in Lithuania, worked on crossover projects, in which he brought together electronic dance music, world music, hiphop, jazz, popular opera repertoire and the centuries-old tradition of Lithuanian polyphonic songs (Lith. sutartinės). ‘I’m always entranced and reach a certain feeling of ecstasy when successful in finding commonalities, to hear the coming together of many different elements,’ said the composer, explaining his inclinations. ‘All the effort, which requires the search for the one and only ‘key’, are justified by an unexpected coherence, the paradoxical feeling that I didn’t create those commonalities – they are there of their own accord.’

Also, at the beginning of their creative journeys Antanas Jasenka (b. 1965) created and performed harsh noise; Vytautas Jurgutis (b. 1976) – post-techno, IDM, glitch music; Jonas Jurkūnas (b. 1978) – jazz, pop, bluegrass, funk, Latin; Egidija Medekšaitė (b. 1979) – alternative rock; Vygintas Kisevičius (b. 1983) – jazz, indie rock and electronic (but perhaps he’s just taking a break now?); Dominykas Digimas (b. 1993) – pagan metal (on vocals and cello!). The pianist Tomas Kutavičius (b. 1964) who began by playing jazz only more than a decade later decided to switch to studying composition. The early experiences of the composers named in this paragraph can be heard in places in their academic compositions and even more so in their work for the theatre, cinema and interdisciplinary projects. However, that is not the purpose of this text, and let’s return to those composers who are active today on those other stages.

How do they themselves understand their ability to turn their hand to different things, the interaction between diverse areas of creativity, how would they term all the music they create and what creative impulses would they point to? Did it sometimes happen that their fans knew about one side of their creative work and were very surprised to find about the other side? One such case will prove to be especially strange.

The composer, lyricist, guitarist, keyboard player Marius Salynas (b. 1975) says that the phenomenon of the popularity of music could be a separate field of study. He began by studying violin and double bass in music school, whereas in his teenage years he played, for example, punk rock and grunge – at the time that kind of music was the most popular, now it has become niche. It would seem that now, having switched from electric to acoustic guitar, he’s more attracted to calm, sometimes meditative or repetitive sound material, let’s say in accompanying singing actors. Very clearly feeling his creative dualism and even eclecticism, from his young days he has been active in various genres and has no intention of stopping. And even though these sides of his creative work are intended for different audiences since it’s musics of different materials and geneses – they still influence one another: more interesting angles and sound structures are to be found in his music of more popular genres while his academic works are sometimes not that academic, suffused as it is with the vitality of other styles.

In her academic creative work Božena Čiurlionienė (b. 1988) often recreates the forms and sounds of early music, music from the middle ages to the baroque. And that’s completely in keeping with what she as a keyboard player, singer and composer does in the group The Skys that plays classical/progressive rock (I didn’t manage to get to the bottom of what’s behind the spelling of the name). The group can boast of the fact that it’s the Lithuanian band that has performed most widely throughout the world, sharing the stage with giants of progressive rock like Rick Wakeman, and has also garnered the most awards abroad – nine in Poland and five across the Atlantic. This composer’s areas of activities are constantly undergoing dynamic change: one day she’s writing a thesis about the change in the understanding of the tritone interval and the symmetrical series in 20th century music or organizing an international conference on philosophy and art theory, and on another day – recording a new rock song with India Carney, the semi-finalist of the Voice of America.

The composer, singer, lyricist, keyboardist, sound director, event organizer, music manager, and educator Ieva Baranauskaitė (b. 1989) can turn her hand to more things than anyone else because she has a greatest bunch of different collectives at a time: Esi (in her own words, jazz, improvisation, contemporary, free, philosophy, avant-garde, silence, poetry), Jazz by Two (jazz, blues, improvisation, pop), In Albedo (jazz, triphop, reggae, drum’n’bass, psychedelic, dub, world, free, fusion, progressive), Such’a’Trip (pop, blues, world, rock, jazz) – those are just the groups of which she’s a leader at present – there were many more. Narratives of old myths, alchemical transformations, the attitudes of human beings in the eternal confrontation of the good and the evil can be found throughout all of her creative work, from the musical, theatrical and interdisciplinary projects, from the above-mentioned groups to her symphonic Master’s work Bazm-e dāstāngo (2016), presenting reflections of the tradition of gatherings of Pakistani story-tellers and writers.

Beata Juchniewicz (b. 1998), who sings and plays guitar and keyboards in the metal group Deliriance, has loved classical music from her childhood days and now feels that both sides of her creative work are very much connected and help one another. She says that generally speaking the whole divide between ‘serious’ and ‘popular’ music most probably arose because of the influence of the music industry on the way music is distributed. Her love for classical music came first, she was 14 when she wrote her first Sonatina for piano and 15 when she began to take an interest in rock. She now weaves in motifs from songs played by her band into her choral and chamber music so that some of her metal songs can help us understand some of the moods and meanings of her academic compositions. And vice versa.

Having chosen the subgenre of gothic/symphonic metal (which, as she emphasizes, is the closest to classical music), she says that in her academic creative work she is a complete chameleon: her tastes and the influences on her music fluctuated from Frédéric Chopin (in her teenage years she was a complete romantic, and even later her fellow students saw her as a representative romantic composer first and foremost and were very surprised to find out about her other side) to Messiaen or her recently beloved György Ligeti. She is now seeking to combine a sonoristic and neoromantic sound, still using Messiaen’s system of modes, in the search for new instrumental colours. However, all of her creative work is united by this gothic thing: dark shades of colours, a melancholy atmosphere, themes of death and horror, sombre grotesques. And there’s nothing surprising here – after all, all that gothic sensibility, all the extremes of rock and metal in principle are ‘metastases’ of the same romanticism stretching out over time.

Raimonda Žiūkaitė (b. 1991), who sings and plays keyboards in the post-gaze/dark pop/alt rock group Eyes Wide Shut, decouples the experience and context of these musics – transferring them from own’s own to an alien one simply does not work. When contemporary academic music concerts are put on in a night club and the musicians shout ‘We’re giving a concert! Quiet there by the bar!’ – for her it’s the same as playing a funeral march in a market place. Which is what she did – there was a time when she was interested in humour, the grotesque in music; besides this performance there was also a composition for the laughter, another one – for the growling female metal singer and the ensemble, playing in Lachenmann-type extended techniques. It seems that she needed that as an antidote to creative depression: having begun with writing pop songs in her early teenage years, she continued with academic music only after beginning her studies at the Lithuanian Academy of Music and Theatre. She then stopped writing songs, she couldn’t manage it, everything seemed too simple but if she tried anything more complex, it just didn’t work. When she started playing rock again, she seemed to recover, although she considers that only something she does in her spare time. In her academic music she makes use of the rational and monolithic processes, where everything is developed from one structural idea – but now her aim is to give her music as many dimensions of the sound colour and effects as possible. And her most immediate plans on the other side of the barricade are to record a solo post-metal/shoegaze album. Her listeners can be quite confused by the dual nature of her character – some are surprised seeing her screaming in some cellar bar, others, who think that she’s just an amateur performer are astonished to find out that she’s even pursuing D.A. degree in music. Even though she herself differentiates between these areas of her creative work, one of her visions now is to bring them together in another way, to dispense with the elementary nature of rock/pop music and the dryness of academic music, to give academic music elements characteristic of rock and metal – the effect of the mass and power of sound. She’s already done something similar – in her Bachelor’s work Levitating Organza for string orchestra (2014) with such concentrated and motoric rock energy which at present do not exist in Lithuanian academic music, except perhaps for the orchestral works of Tomas Kutavičius mentioned above.

Andrius Šiurys’s (b. 1991) acquaintanceship with composition didn’t begin with his academic studies but with electronic music. He began to write academic music only after beginning his Master’s studies at the Lithuanian Academy of Music and Theatre in 2013. Before that he didn’t know very much about that sort of music and felt himself to be an outsider because of his lack of knowledge; on the other hand, he really didn’t like the music he’d heard by Lithuanian composers at concerts and in exams, and that provided the greatest impetus for him to create his own music. At the time, he had a lot of creative anger and wrote very expressive and technical music. He now says that perhaps his music has slowed down and become more ‘serious’ – but he feels that he may perhaps go back to his earlier, more authentic self. What is the connection of his academic creative work with the music played by his groups – Delasferos (vocal chill out, ambient, triphop), the Electronic Music Trio with the composers Jonas Jurkūnas and Martynas Bialobžeskis (noise, industrial, glitch) and Galvos oda (Head’s Skin; ‘an absurd noise’)? His listeners, acquainted with all the different areas he’s involved in, say that they share an oddness, a strange darkness and bitterness. Not specially aiming for this, he himself feels the divides and the inevitable overlaps; the tools of various genres are used in his music for the theatre and in some chamber electroacoustic compositions – but it’s precisely in his academic notated music that he allows himself to experiment the most. And what about Head’s Skin then? Well, he himself finds it strange when anyone tries to figure it out, few people like it and they find it difficult to comprehend how a ‘serious’ composer can write something so absurd…

Ensconced in more peripheral territory of non-academic creativity is the composer, improviser, sound and video artist Gailė Griciūtė (b. 1985). The processes involved in her composing were radically influenced by discoveries made while improvising; improvisational-aleatoric episodes in her written music help her to elicit an organic flow. At the same time, the improvisational sphere of her work is as heavily influenced by composition – these various constructional solutions in an improvisational context, an exceptional feel for the whole form. You might ask what’s so special about a composer that improvises? Well, there are her chamber compositions woven from ascetic strokes and silences. And there are her fierce improvisational volcanoes on piano (usually heavily prepared) – paradoxically, no matter how much she tries to rein in her emotions and leave as few sounds as possible! – since a lot depends also on the energy of other improvisers making music together with her (like the electronic musician Antanas Dombrovskij, the drummer Arnas Mikalkėnas, Yumiko Yoshimoto, a guitarist from Japan, or the Lithuanian Art Orchestra led by Vladimir Tarasov). If you listen to her different kinds of music without knowing whose they were you wouldn’t be able to tell that they belonged to the same person. Listening for a second time more intently, you would recognize some common features – sounds, details and shapes. And once you were in possession of all the facts, you might perhaps think that it was a perfect reflection of yin and yang in the music of one and the same person.

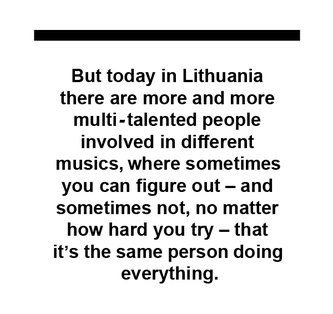

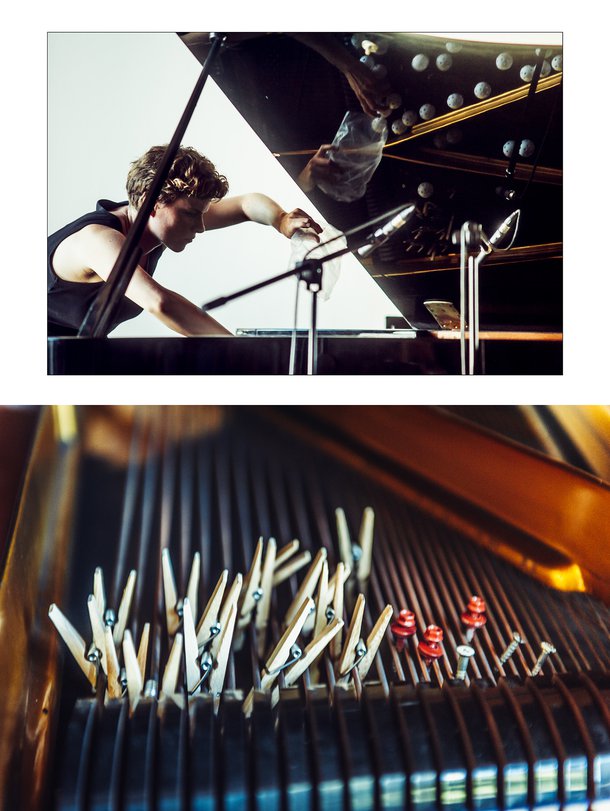

But let’s return to the more ‘mainstream’ spheres of non-academic music. In this regard the best known of those who can turn their hand to many things today in Lithuania is Bjelle (b. 1991), whose real name is Raminta Naujanytė. She is a composer, singer, lyricist, guitarist, keyboardist, choir leader, educator, event, radio and TV presenter, piano tuner and renovator, painter… in other words, a Renaissance person. She sings in popular musicals, she’s much in demand both by indie internet video channels and the national broadcaster Lithuanian National Radio and Television – to perform well-known songs by other composers or to present the national song competition for children and young people.

Constantly experimenting, changing both the style of the music Raminta Naujanytė-Bjelle writes and her voice (her voice matured naturally: from her earlier pure bell-like sound in the direction of a more rich and deep one), as well as her stage image (from that of a girl from the provinces to a diva), Bjelle began writing songs when she was 6 and by the age of 9 she was convinced that one day she would be an academic composer. She took an interest in various styles and absorbed their influences. In her teenage years she was active on the rock scene in her native town of Ukmergė, later she sang what was called ‘sung poetry’ in Lithuania and Eastern Europe, and ‘bard songs’ in Russia, and simply folk in America (and she hasn’t given up this type of music to this day); at that time she wrote a patriotic song about a brother that rides off to war – it became one of those songs that all of Lithuania knows. Her debut album in 2017 Kas tu toks (Who Are You) was already an example of refined art pop. She is recording her second album now – who knows what’s going to be in it but one thing is clear – we’ll have to ask the same question again: so who exactly are you?

In presenting her work, Bjelle differentiates between these areas. In fact, in her case it’s again hard to believe that everything is composed by just one person. (That’s what happened to the author of these words: from the beginning he knew that there is Raminta Naujanytė and there is Bjelle but didn’t realize that it was the same person.) Although one could find some connections between the three a capella songs from the above-mentioned album and her compositions for choir of which she has written over a dozen; the first of that kind, and in general her first academic composition, came into being when she was already twenty years old. Even though she had been thinking about academic composition for a long time, one could say that the well-known composer and choir leader Vytautas Miškinis gave her a push, so to speak, for her to put her plans into effect. When she asked him for a composition for the girls’ choir she was the director of, he said – try and write one yourself.

In both her vocal and instrumental music, she pays a lot of attention to the sonoristic principles of compositions, to the psychoacoustic analysis of melodies, she says that ‘every listener when hearing a sound, not necessarily in the right place and at the right time, or perhaps one that is of no consequence at all, will be made to think and awake in themselves a deep-seated ability to listen more closely’ (for example, in listening to her Bachelor’s work Sohum for string orchestra (2015), one has to hold one’s breath and follow the threads of the ppppp dynamics for over two and a half minutes, for almost a third of the length of the work).

In the meanwhile, her identity in her other area of creative work, even though forever changing, remains recognizable – perhaps similar to the constantly experimenting great songwriters like Joni Mitchell, Kate Bush or Esperanza Spalding who are changing and remain the same. But here come the latest news: Bjelle disbands her rock group, Bjelleband, decides to perform solo from now on – and goes to Reykjavik to study electronic music and sound technology at the Icelandic University of the Arts. We will wait – those studies, as well as the very experience of Iceland, will infuse her music with yet another colours and meanings.

In 2017 the newest firework to light up the sky was Monika Zenkevičiūtė (b. 1995), who began playing electronic music under the stage name of Monikaze while studying composition. She began – and immediately went off to Bristol to play in the cradle of triphop to show how it should be done today. She wasn’t striving to follow some specific electronic music subgenre, even though, of course, she didn’t invent everything from scratch. It all began with the intention of having some fun and testing her abilities – taking on sound models of many styles, combining them in various ways and clearly adapting some principles and skills of development and alternation of structures from the acacademic composition. The rhythms of IDM or triphop, ethereal ambient sounds, her own vocalizing (listen, say internet commentators, to how that birdie sings on top of bass) are arranged into such focused and meticulously detailed ‘orchestrated’ forms that there’s nothing to compare it to – it would seem that there’s no one else playing this kind of electronic music. Let’s simply say that this is a case of mathematics meeting romanticism: there are always the through-composed forms, electronic tone poems, details ‘sticking into acupuncture points’, and pulsations flying farther off into the distances.

Well, there aren’t going to be any conclusions since I’m already late in submitting this text, which is quite long enough as it is. So, we’ll just have to wait and see who will surprise us and with what, who will turn their hand to ever more things. And it would seem some are already beginning doing that.

Translated from the Lithuanian by Romas Kinka